Seaways Free Article: Shiphandling: The Beautiful Game

Introducing The Nautical Institute's latest publication

by Captain Grant H Livingstone SNAME FNI

and Captain George H Livingstone FNI

The beautiful game is a term inspired by the outstanding Brazilian footballer Pelé (Edson Arantes do Nascimento). It arose because of his artistic execution. On the pitch, Pelé loved the game with the same fervour as those in the stadium who were cheering him on. But Pelé did not begin his career with artistic execution.

After he joined his first professional team, Pelé recalled: There was no moment when things started to turn around for me. There was no epiphany or great triumph. Instead, I just kept training, kept doing my drills, kept focusing on football (Pelé and Winters, 2015). Mastering fundamentals, combined with passion and dedication, is how Pelé achieved artistic execution. The same holds true in shiphandling.

Knowledge and 'feel'

As in football, shiphandling is revealed in its execution; not just technical knowledge, but also skill. The best shiphandlers understand and endorse the science, but nearly always talk about the ‘feel’. That’s the remarkable way in which the human brain assimilates experience and develops motor skills and cognitive deduction into artistic execution, fuelled by passion. The good news is that someone who has less innate aptitude can, with passion, determination and training, become a competent shiphandler.

The shiphandler executing at the highest level senses what is happening and anticipates what will happen next, balancing forces seamlessly and executing manoeuvres almost perfectly. When that happens, shiphandling becomes the beautiful game.

Advanced and artistic execution cannot be achieved without fundamental knowledge. Fifty years ago, when there were far greater numbers of smaller ocean and coastwise trade vessels, it was common for Masters to handle their own vessels. A Master’s shiphandling skill was not only essential; it was the professional standard.

Fundamental change in three areas of the maritime industry – ship size, technology and liability – has all but eliminated that standard. Today, most Masters are not afforded the same opportunity to handle their own vessels, with the notable exception of passenger ships and coasters. The consequence has been a significant loss of professional shiphandling knowledge and skill among most mariners. Considering the astronomical liability for all parties involved in the movement of ships in the 21st century, this matters a great deal.

Shiphandling is a long-established subject of conversation among mariners. We hope to shed greater insight into areas of shiphandling that have changed or become outdated, or which would benefit from new study. This is not a comprehensive A–Z shiphandling book. The reader will discover a primer on managing fundamentals, strategic thinking, effective commands and managing emotions and pressure, in addition to inertia and momentum, assist tugs, zero visibility, turns, anchoring and distractions. Student shiphandlers may be surprised to learn that successful shiphandling depends on much more than shiphandling skill.

Where next?

There is no single source of shiphandling knowledge. It is our hope that this volume may add value to broader study. Each chapter and section can be reviewed independently and used as a reference when needed. The intent is to fortify mariners with easy-to-understand explanations focused on fundamental aspects of manoeuvring vessels.

Mariners have always had professional discussions on a wide variety of maritime subjects, including human factors studies of bridge resource management (BRM). However, from the authors’ combined experience of 20,000 ship piloting manoeuvres, far less attention is paid to the debilitating effects that anger, fear, anxiety and panic can have on decision making on the ship’s bridge. Nevertheless, mariners have long borne witness to the often-negative outcomes arising from those emotions. Under the weight of ever-increasing professional liability, and with bridge VDR technology recording everything a mariner says and does, it is not surprising that professional discussions about mariners’ fear, anxiety, anger and panic are not taking place on the bridge. The study of shiphandling must include understanding the emotional-psychological state required to manoeuvre successfully the largest (and smallest) floating objects on the planet. This book addresses that directly.

In the past, professional mariners tended to overlook emotions and pressure in shiphandling studies, as if they were not an integral part of decisions. ‘Suck it up kid, it’s a contact sport,’ was the traditional advice for dealing with fear, panic, anxiety and pressure. These negative emotions and pressure can block access to the criticalthinking skills that shiphandling demands, often when they are needed most. Understanding emotions and pressure is as foundational to shiphandling as understanding wind and current.

The shiphandling content of this book was determined by mariners at sea, for mariners at sea. A shiphandling survey conducted by The Nautical Institute in March 2023 asked mariners to consider their experience in shiphandling. It asked them two questions:

- What were the most challenging elements to learn theoretically?

- What were the most challenging elements to execute practically?

The collective answers to those questions revealed common challenges for professional mariners studying and executing shiphandling. The shiphandling content of this book is a response to those questions and challenges.

Managing emotions

The authors discovered early on – long before we imagined handling ships or tugs – that we had a strong aversion to hitting anything with a boat. That aversion revealed itself when learning to handle small sailing boats and crashing into docks, rocks and other sailboats. It was one part embarrassment, two parts panic: embarrassment, because everyone was watching; panic, because we did not know how not to crash (and everyone was watching). Decades later, we can still tap into that awful feeling conning small boats banging into objects, but now it’s three parts embarrassment because we have learned a lot about emotions and the game.

Considerable study of the human element has taken place and study of human factors is evolving. Harvard Business Review (HBR) executed a large-scale study of what selfawareness is, why we need it and how to improve it (Eurich, 2018). That HBR study identified two categories: internal and external self-awareness – seeing ourselves objectively and getting objective feedback to understand how others see us, respectively. Increased self-awareness improves our understanding of why people behave the way they do and of the relationship between behaviour and consequences.

This book aims to focus on how our own emotions affect our own decision making, particularly under stress, which is key to executing good shiphandling decisions.

Clinical studies show human beings are subjective, not objective, by nature. This requires education and training to mitigate. It is unlikely that the average person can process information with complete objectivity without education and training.

Factchecking emotions

Emotions are natural and serve as signals: happy, sad, angry, depressed, frightened. These signals have helped humans to survive for thousands of years. To oversimplify, the brain interprets/processes sight, sound and senses and sends out information to the rest of the body, resulting in feeling, emotion, perception and action. This is known as stimulus perception followed by a behavioural response.

The signals flow through innumerable biological and neurological pathways to and from our brain before manifesting as a physical or emotional response.

Much of this occurs at a subconscious level, in mere hundredths of a second. Before we have a chance to consider, we’re already experiencing the emotion (Schreuder et al, 2016). Without objective self-awareness and self-differentiation, negative emotions can hijack responses. Objective decision making is foundational to effective shiphandling: all emotions should be fact-checked.

Anger

Take anger, for example.

Living and working on tugboats and ships for extended periods of time naturally creates stress. It is a challenge to maintain emotional composure over long periods of time in a small space, away from home, family and friends.

Anger is a motivational emotion. In certain situations, a temporary burst of anger may give the individual an emotional and physical boost, determination and adrenaline. It focuses our attention on the obstacle in front of us by diminishing our peripheral senses and increasing our risk threshold, and triggers blood flow to our extremities. All of these may be exactly what one needs to succeed in a fight or extreme situations.

What if getting out of extreme situations depends on unemotional objectivity and unbiased facts? In shiphandling, anger increases our risk threshold. The blood flow to our extremities competes with the blood supply to our brain. Angry people find angry messages convincing. Anger commonly carries over from a past event and is likely to affect our judgement and decision making in the current situation, whether it’s applicable or not.

When we get angry, we may blame others for the problem and get even angrier. Anger interrupts cognitive processes and hijacks our attention, skewing judgement. By hijacking our cognitive process, our decision making for the task at hand is distracted and slowed down. Anger and chronic stress also negatively affect our memory.

Others often view angry people as hostile, domineering, rude and uncooperative. Respect, cooperation and teamwork can disintegrate, causing communication and information exchange to cease.

If I am hijacked by anger and lose self control and start yelling, I stop hearing anyone else and become further critically distracted from the task at hand. Yelling seldom improves communications or solves problems: it creates more stress and hinders problem-solving just when the opposite response is needed.

If I am angry on a ship:

- I may get tunnel vision;

- I may blame others for the problem;

- I may feel overconfident and take greater risks;

- my decision-making process may become distracted;

- anger and decisions in past situations may inappropriately carry over to;

- influence current situations;

- will alienate the team or individuals around me; and

- communication and information may cease.

Nothing in shiphandling is improved by becoming angry: quite the opposite. Anger usually begins with irritation, which can be just as distracting as anger. We are human, however, so at times we become irritated and angry. The good news is we can learn to manage those and other emotions that affect shiphandling decisions. Learning how to manage emotions and pressure is covered in depth throughout this book.

Shiphandling

Rules and exceptions

The first rule of shiphandling is there is an exception to nearly every rule. There are so many elements encompassed by the subject of shiphandling that if you were to devote all your time to mastering the academic science of it, there would be no time left for practical application. It is impossible to begin a career with the knowledge and expertise that can only be acquired throughout a long career of shiphandling. The shiphandler can advance their knowledge and expertise at an accelerated rate with a thorough understanding of the principles of shiphandling.

Experience is a wonderful teacher, though often a very slow one. In the course of time, it will instil into a seaman’s mind a considerable knowledge of the capabilities and behaviour of his vessel under varying circumstances – her strength, her carrying capacity, her stability, or, in other words, her sea qualities.

This mode of obtaining knowledge is, however, far too costly for the intelligent seaman of today. He knows that many a good ship, and what is worse, many precious lives have been lost before it has been acquired, and all through pure – though it would be unjust to say, wilful – ignorance. (Walton, 1901)

Begin the journey by learning how to manage the varied elements, such as:

- momentum and inertia;

- speed, wind and current;

- anchors and rudders;

- restricted waterways and turns;

- tug types and placement;

- tug commands;

- tug and ship crew safety;

- berthing and unberthing; and

- traffic management.

Mistakes will be made often; dedication, patience and passion will be required to follow through. But don’t be discouraged: shiphandling is a numbers game. The more ships you can move in ports, bays and rivers with varied manoeuvres, the more ability you will acquire, if your knowledge is fundamentally sound. The journey is rewarding and begins with a solid understanding of the fundamentals. Maintain a journal of that journey to learn and improve.

Managing fundamentals

The old-fashioned method of ‘beginning at beginning’ of the subject has been adopted as the only trustworthy way; and while endeavouring to cover as much as possible, the aim has been to condense the matter as far as compatible with clearness, to present it in a language easy enough to understand by every seaman. (Walton, 1901)

When a subject is complex, you must understand the fundamentals if you are to advance to higher levels. It is folly to attempt advanced execution without excellent fundamental knowledge and practice, particularly in shiphandling. Don’t get sidetracked trying to execute complex manoeuvres that demand advanced levels of training and experience. Being impatient during training at the beginning of a career and bypassing the fundamentals will only erode and undermine your skill and execution when it matters most, later in your career.

Strategy

In the world of business, strategic thinking is foundational for success. Strategic thinking is also foundational for successful shiphandling; the two are interchangeable. Successful strategic thinking identifies threats and vulnerabilities and produces clear goals, adapting to the everchanging marine environment.

Strategic-thinking skills enable you to use critical thinking to solve complex problems and develop a plan balancing actions and ideas against consequences and results. An ability to envisage new solutions and to continually reinvent are requisites for successful shiphandling.

Managing speed

One fundamental key to every aspect of shiphandling is speed. The last generation of mariners warned that in shiphandling there are three things to watch carefully:

- Speed;

- Speed;

- Speed.

Speed is like salt: easy to pour on, difficult to take off.

Speed can become problematic and not only on full ahead: 1 knot can be excessive if there isn’t enough room to stop. Appropriate speed (not to be confused with International Rule no. 6, or Colregs) is the speed at which the shiphandler can reasonably expect to stop the ship with anchors or engines or tugs, prior to allision or collision (in an emergency, that may require all three options). If inbound at sea buoy, multiple miles outside a port, sea speed may be appropriate as there are miles available in which to stop. In a narrow harbour with berths close on either side, speed should ideally be such that the ship’s course and direction can be properly controlled with the use of engine rudder and tugs. Exceptions are usually related to weather, current or mechanical failure.

Shiphandlers traditionally relied on their eyes to judge speed when manoeuvring ships. Today, ECDIS, radar, PPU and handheld electronics all provide the shiphandler with accurate speed readings. The unintended consequence is that the important habit and skill of visually monitoring speed is being lost. Do not underestimate the validity of visual estimation!

A 2021 research report in the European Journal of Neuroscience on subliminal perception (the ability to discriminate visual stimuli not consciously seen) suggests that, rather than being a separate unconscious capacity, subliminal perception is based on similar processes to conscious vision (Railo et al, 2021). The shiphandler should pay close attention to relative movement directly on the beam, and practise and develop the skill of visually observing and estimating speed and other ship motion.

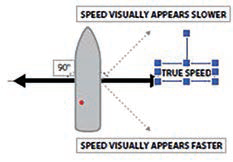

To estimate speed visually, the observer must be looking abeam exactly 90 degrees to the ship’s keel. With headway, if the shiphandler looks slightly forward of the beam to objects on the near horizon, the relative speed will appear to be less than it is. If the gaze is slightly aft of the beam, the relative speed will appear greater than it is. When close enough to any berth or land, the old advice to imagine someone walking alongside the ship as an estimation of speed is still helpful. Walking speed for the average person is about three knots.

With practice, the shiphandler can become accurate at visually estimating speed. The greatest benefit of that habit is that the shiphandler’s peripheral vision begins to pick up changes in ship speed naturally (subliminal perception), even when not looking. This skill provides the shiphandler with speed information as instantaneously as the bridge instruments.

Ships do not control speed – shiphandlers do.

About the authors

Twin brothers Grant and George Livingstone graduated from the California Maritime Academy in 1980 and both embarked on a decades-long career at sea, becoming expert on pilotage, shiphandling, offshore tug operations and ocean towing.

Over the course of 40 years at sea, George has sailed on a wide variety of vessels, ranging from US-flagged ships to harbour and ocean tugboats. As a pilot, he was active in various leadership roles, from the Harbor Safety Committee to State Pilot Commissioner, roles in which he made important contributions to the training of pilots and the development of safety management. His career includes 13 years of service with the San Francisco Bar Pilots, as well as a period in the role of Vice President of The Nautical Institute. Despite retiring from the San Francisco Bar Pilots in 2021, George has remained active within the maritime sector since through his writing and as a consultant involved in the training of tug captains and pilots.

Grant has worked as a pilot for Jacobsen Pilot Service in the Port of Long Beach, California, since 1991, and he assists in the training of all new-hire pilots in addition to his own duties. Within that time, he has undertaken more than 16,000 documented ship moves. Additionally, Grant has provided extensive training to Mexican pilots and Azimuth Stern Drive (ASD) tug captains on behalf of simulator training provider Marine Safety International. He has helped the Maritime Research Institute Netherlands (MARIN), a leading European hydrodynamic and nautical research facility, to develop an emergency manoeuvring simulation package for ASD tugs, including the production of a training DVD. He has provided similar training assessments to Pacific Maritime Institute, Boluda Towing and the ports of Progreso and Veracruz, Mexico. He has also worked for South Coast Tugboats.