Free Article: The IMO: roles; structure; outputs

What it is and why it is important to the Nautical Institute’s members

by Capt Chris O’Flaherty AFNI, The Nautical Institute Senior Technical Adviserand Natasha Brown IMO Head of Outreach and Communications Office

A (very) brief history

The regulation of international shipping requires significant cooperation between the many shipping nations of the world. Starting nearly 2,000 years ago, the first trans-national maritime codes emerged across the Roman and Byzantine empires. By the 16th century, Admiralty Law was becoming a distinct sphere of jurisprudence, with small groups of sovereign countries occasionally cooperating to develop common codes of conduct, often in parallel with securing their international commercial interests.

International maritime rules were also brought in to regulate maritime warfare. For example, the Paris Declaration of 1856 abolished privateering and declared that neutral goods in shipping are not liable to be captured by an enemy, unless they are contraband of war. In contrast, the rules overseeing commercial maritime transport continued to exist primarily in national regulations, with the laws governing a specific voyage normally being those of the flag state of the ship concerned.

An attempt in 1889 to set up a permanent international body for shipping failed due to rafts of national protectionism. The sinking in 1912 of the RMS Titanic, with the tragic loss of life that ensued, delivered a change of course towards increased cooperation. This led to an international conference which agreed the 1914 Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS). The League of Nations subsequently took on the task of coordinating maritime cooperation, for example through the Convention and Statute on the Regime of Navigable Waterways of International Concern, negotiated in 1921.

The inception of the United Nations in 1945 presented a new opportunity for global cooperation. In 1948 an international conference in Geneva adopted a convention to formally establish the Inter-Governmental Maritime Consultative Organization (IMCO). This convention entered into force in 1958, with a headquarters in London, and the new organisation began operations the following year. The aims of IMCO centred on safety and navigation, as well as delivering commercial shipping globally without discrimination. IMCO was renamed in 1982, becoming what we know today as the International Maritime Organization.

Today, the current aim of the International Maritime Organization (or IMO), is:

‘To provide machinery for co-operation among Governments in the field of governmental regulation and practices relating to technical matters of all kinds affecting shipping engaged in international trade, and to encourage the general adoption of the highest practicable standards in matters concerning maritime safety, efficiency of navigation and prevention and control of marine pollution from ships’

The present mission of the IMO, set out in their 2024-2029 Strategic Plan, is to: ‘Promote safe, secure, environmentally sound, efficient and sustainable shipping through cooperation by adopting the highest practicable standards of maritime safety and security, efficiency of navigation and prevention and control of pollution from ships.’

The current priorities of the IMO include:

- Improve implementation (of IMO instruments, regulations and procedures).

- Integrate new and advancing technologies in the regulatory framework.

- Respond to climate change.

- Engage in ocean governance (including marine litter and prevention of illegal and unregulated fishing).

- Enhance global facilitation and security of international trade.

- Address the human element (including seafarer support and ensuring seafarer wellbeing).

- Ensure regulatory effectiveness (using data and data analysis for decision making).

- Ensure organisational effectiveness.

What is the remit?

Back in 1948, the first task of the new IMCO (now the IMO) was to thoroughly update the SOLAS convention. This was delivered on 17 June 1960.

Thereafter, the IMO negotiated a range of conventions covering maritime safety, security, pollution (including prevention, liability and compensation), seafarer training, communications, hazardous cargoes, salvage and even the measurement of tonnage. Key IMO Conventions include:

|

Name |

Number of States Party |

Percentage of World Tonnage |

|

International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), 1974 |

168 |

98.63% |

|

International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from ships (MARPOL), 1973 |

161 |

98.61% |

|

Convention on the International Regulations for the Prevention of Collisions at Sea (COLREGS), 1972 |

164 |

98.63% |

|

International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW), 1978 |

167 |

98.63% |

|

Convention on the Facilitation of International Maritime Traffic (FAL), 1965 |

130 |

95.89% |

The IMO presently oversees 32 international Conventions, plus 21 Protocols (major amendments – see terminology box).

There is one key maritime convention that does not fall under the remit of the IMO. The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and its predecessor conventions are negotiated and overseen by the United Nations. That said, many of the articles in UNCLOS refer to the ‘competent international organisation’ relating to matters such as safety of navigation – in effect, referencing the IMO.

To address one often asked question, the IMO has no remit to engage in activities that may be considered as directly affecting the trade or commercial aspects of shipping. This is due to the number of ‘reservations’ submitted by states party to the original IMCO Convention of 1948, which made clear that IMCO/IMO interference in the trading aspects of shipping was not acceptable. In consequence, the modern IMO confines itself mainly to technical issues.

Who can attend?

As a specialised agency of the United Nations, the IMO is a membership organisation in which representatives of national governments (for example, in the case of shipping, Flag, Port and Coastal States) make the formal decisions.

Each of the 176 member states is represented at the IMO by a delegation. The Heads of Delegation are often the Ambassadors or High Commissioners of the various diplomatic missions in London, who ‘present their credentials’ to the Secretary General on taking up their post.

In order to manage the busy workload of maritime matters, many delegations assign a ‘Permanent Representative’, who becomes the visible presence of that state at almost all IMO meetings.

All delegations can be augmented by technical experts from their nation’s civil service or shipping industry who have expertise in specific subjects as they arise. This ensures that the regulations produced by the IMO are of the highest quality. At some IMO Committee meetings, it is not unusual to see delegations swell to more than 10 members, or even up to 30, once subject specialists are included.

Expert input to the IMO is also delivered by the delegations from some 160 inter-governmental and non-governmental organisations accredited with ‘Consultative Status’. These range from representatives of the Port State Control MoUs, through telecommunications, shipbuilding and fuels organisations, to environmental NGOs and professional bodies such as The Nautical Institute.

Committee structure

The highest governing body of the IMO is the Assembly. This consists of all 176 member states. It meets once every two years to set the overall work programme and budget. Decisions are taken on the basis of one-member-one-vote, regardless of size of country or of registered tonnage.

The Assembly then elects 40 states who form the Council (to be expanded to 52 states at a future date). These elected states meet approximately every six months to supervise the work of the committees and of the IMO Secretariat, including the appointing of the Secretary General of the IMO, subject to approval by Assembly.

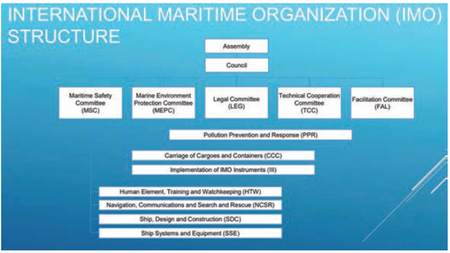

The main technical work of the IMO is carried out by five committees:

- Maritime Safety Committee – navigation, safety, maritime security, crewing, ship construction, cargo handling and marine casualty investigations.

- Marine Environment Protection Committee – environmental matters.

- Legal Committee – legal matters.

- Technical Cooperation Committee – implementation of technical cooperation projects.

- Facilitation Committee – Focuses on the elimination of unnecessary formalities and of ‘red tape’ in international shipping, including the balance between good marine security and efficient trade.

While the main committees debate relevant maritime matters in open session, the detail of drafting and checking maritime conventions and codes is delegated to drafting or working groups. All member states and international NGOs with consultative status can attend all meetings of committees and sub-committees and participate in working and drafting groups.

The work of the Maritime Safety Committee and the Marine Environment Protection Committee covers a very broad range of specialist subjects. Between them, these two committees have seven subcommittees who look into the minutiae of maritime matters within their speciality, and advise the main committees of the best actions to take.

Every committee and sub-committee also uses a multitude of correspondence groups, inter-sessional working groups, and ‘breakout’ working groups of subject matter specialists to conduct the detailed drafting and review of technical conventions, codes and agreements.

How decisions are made

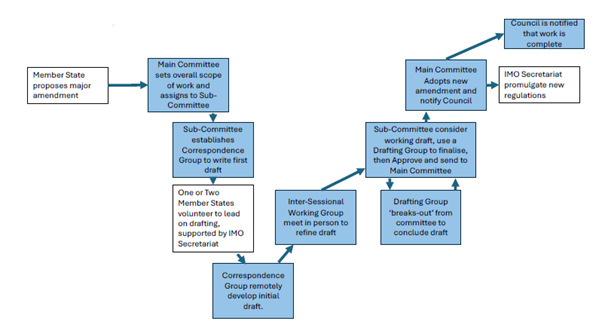

By way of example of how a major amendment might be progressed:

Example progress of a major change to an IMO instrument

If the outcome is a new instrument, then the treaty will have to be ratified by a certain number of member states before it comes into force. The number of states required is specified in the text of the instrument, and will often represent a specified level of global tonnage.

However, most IMO conventions include the so-called tacit acceptance procedure – meaning that a new amendment will enter into force on a set date, unless a sufficient number of states object to the amendment within a given period (usually 10 or 12 months). In practice, this means most amendments enter into force on the chosen date. The committees, and the Council itself, place a great deal of emphasis on reaching consensus. Almost every matter at the IMO is agreed by every member, and voting is very rare indeed. This exemplifies the outstanding levels of cooperation achieved across flag, port and coastal states in pursuit of common aims for the safety, security and environmental protection of our maritime workplace.

The IMO Secretariat

To support the member governments, the IMO has a secretariat of just under 300 United Nations civil servants who provide much of the staffing effort behind every development in maritime safety and regulation.

The IMO is headed by the Secretary General, currently Mr Arsenio Dominguez, who is responsible for the overall management and running of the organisation, including its budget. The Secretary General of the IMO also reports on maritime matters to the United Nations.

The four shipping-focused divisions of the IMO Secretariat are:

- The Maritime Safety Division: Responsible for operational safety, the human element, technology, cargo and security.

- The Marine Environment Division: Responsible for climate change, biosafety and marine pollution.

- The Technical Cooperation and Implementation Division: Responsible for coordinating and executing a host of projects which support Member States to implement IMO instruments.

- The Legal Affairs & External Relations Division: Responsible for legal affairs, including the Legal Committee’s work, advising on the legal wordings of IMO instruments, external relations including protocol matters and checking delegations’ credentials; as well as IMO’s outreach and media.

The essential support functions at the IMO are divided between the secretariat divisions:

- The Administrative Division: responsible for human resources, information technology support services, and the publishing of IMO instruments.

- The Conference Division: who arrange the vital facilities and interpretation/translation (the IMO works in six official languages) which allows IMO decisions to be debated and then approved.

The Nautical Institute at the IMO

The Nautical Institute has a long association with the International Maritime Organization. As testament to our longstanding and close cooperation, three previous Secretaries General have been elected as Honorary Fellows of our Institute: Chandrika Srivastava (1985), William O’Neil (1996), and Rear Admiral Efthimios Mitropoulos (2002).

In the early years after The Nautical Institute was founded in 1972, we were able to contribute our professional opinions to the IMO through existing IMO consultative organisations with which we had close ties. The NI’s 1985 AGM was held in the IMO Headquarters building, epitomising our close links with the organisation. These links were further cemented in 1994 when the NI’s new publication Bulk Carrier Practice became a core text at the IMO’s Sub-Committee on Dangerous Goods, Solid Cargoes and Containers.

By 2008, The Nautical Institute was in a position to devote a fulltime resource to IMO engagement. We applied for Non-Governmental Organisation Consultative Status, which was formally approved in 2009. While we cannot vote on any matter, we can attend all IMO committees and we advise and influence the governmental delegations.

The Nautical Institute’s Research and Relationships team now lead on our IMO engagement, with one member of the full-time NI staff focused on IMO cooperation. This engagement is overseen by our IMO Committee, which is appointed by the NI’s Council, and is led by Capt Robert McCabe FNI. The hard day-to-day work of representing our members at many IMO Committees, sub-Committees, working and correspondence groups is achieved through NIHQ staff and a network of volunteer members who have offered their specialist knowledge to help with the many subjects considered by the IMO. These members are accredited at the IMO as official Nautical Institute delegates.

The Nautical Institute regularly submits specialist papers and comments on IMO instruments. These IMO instruments then set many of the regulations that keep our members safe at sea, and which protect our living and our working environments. As a key voice for the human element at the IMO, The Nautical Institute has duly carved for our members a professional position of significant regulatory influence, which we work hard to maintain.

Nautical Institute President Trevor Bailey FNI meets with IMO Secretary General Arsenio Dominguez at IMO headquarters, September 2024

Click on the options below for more information on the IMO.

The United Nations and the IMO use a series of legal terms to describe various international regulatory documents. As a guide:

Treaty: An international agreement concluded between States (or International Organisations) in written form intended to create rights and obligations enforceable under international law.

Convention: This term is generally used for formal multilateral treaties with a broad number of parties. Conventions are normally open for participation by the international community as a whole, or by a large number of states, and are considered binding on those who ratify them.

Protocol: Protocols are normally used to amend, supplement or clarify a prior convention or treaty.

Agreement: A written codification between states of principles or rules which are not necessarily intended to be legally enforceable between the parties.

Code: Detailed information, rules and regulations agreed between states party to an overarching treaty or convention, often covering technical or specialist matters.

Guidance: An advisory document that has no formal legal status, but which can be quoted when highlighting actions to maintain risks at a level that is As Low as Reasonably Practicable.

- 176 Member States and three Associate Members.

- 160 observer organisations providing specialist advice.

- 99% of world shipping tonnage is represented at the IMO.

- The IMO regulates over 50,000 merchant ships trading worldwide.

- Top flag states at the IMO, by tonnage: Panama; Marshall Islands; Liberia; Hong Kong, China; Singapore.

- Top crew supply countries at the IMO: China; Philippines; Indonesia; Russian Federation; Ukraine.

- Top shipowning countries at the IMO: Greece; Japan; China; Germany; Singapore.

- Top shipbuilding countries represented at the IMO: China; Japan; Republic of Korea (these represent 90% of total shipbuilding).