202515 Hazard in plain sight causes catastrophic injury

Providing learning through confidential reports – an international co-operative scheme for improving safety

As edited from MAIB (UK) report no. 11/2024

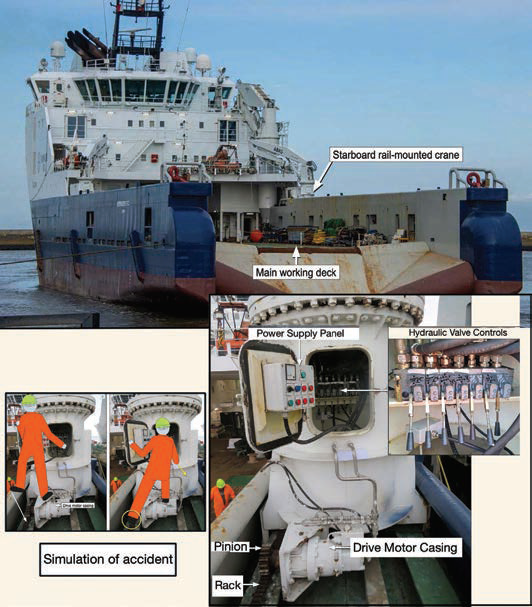

A survey/supply vessel was alongside preparing for a contract, for which several items of deck gear and machinery had to be moved. A lifting plan and permit to work had been completed and the deck crew informed of the work to be done.

A deck officer and a fitter went on deck to move several heavy items using the starboard rail-mounted crane. The officer climbed up the ladder to access the crane and used the local hydraulic valve controls in the crane pedestal to manoeuvre the crane. This was the only way he knew how to operate the crane and was the way he was shown in his arrival familiarisation training.

After repositioning two loads on the main deck, a third lift was initiated. In order to see both the fitter and the load to be moved 4m below on the main deck, the officer stood with his left foot on the inboard bulwark and his right foot on the crane drive. At one point, he shifted his left foot from the bulwark to the crane’s travel rack. He felt something pulling at the left leg of his overalls, which unbalanced him.

He held onto the crane travel lever for stability, but this caused him to unintentionally pull it further backwards, which increased the speed of the crane’s traverse on the rack, and his left foot and leg were dragged into the rack and pinion drive. He let go of the travel lever, which stopped the crane.

The fitter climbed up to the crane’s rail and found the victim lying on his back with his left leg trapped between the rack and pinion. The victim, still conscious, instructed the fitter to move the crane forward; this action freed his leg, which was severely mangled below the knee. The alarm was quickly raised, and the vessel’s first aid team was activated. Soon after, a helicopter transferred the victim to hospital, where his leg required amputation below the knee.

The investigation found that the crane manufacturer’s operations manual, which was available on board, stated that the local controls in the crane pedestal were for emergency use only. Normal operation was to use either the bridge control station or the crane’s remotecontrol unit. The company’s Safety Management System (SMS) made no reference to ship-specific operating instructions as there were none. The practice of operating the crane with no guardrails or restraints while working at height, and near the unguarded rack and pinion gearing, was a clear sign that the process was flawed. The crew indicated that they had the freedom to challenge on board practices, but they did not raise the issue of the operation of the cranes using the local controls as they considered it ’normal’. This demonstrated not only an ignorance of the manufacturer’s instructions but a certain blind eye to unsafe acts or unsafe conditions.

Lessons learned

- Why is it so easy to see a hazard after an accident? Seeing hazards where you habitually work is not effortless – you have to work at it. Open your mind and look ‘with new eyes’ at each task. Is there danger?

- Although generic instructions and practices in a company’s SMS are a good first layer of protection, every vessel should have ship specific procedures that address the specific hazards of that vessel. No one knows the ship better than the crew, so get to work on your ship specific procedures

Editor’s note: Over ten years ago, when I first boarded a small dredger I have since helped operate as Master, there was only one shipspecific procedure. Over the years, we have added to our library of ship specific procedures (we now have a total of 32) and have also developed several ship-specific ‘hazards’ that we use for familiarisation training and continual reference. These things take time and are a matter of continual improvement.