202509 Progressive flooding sinks tanker

Providing learning through confidential reports – an international co-operative scheme for improving safety

As edited from KMST (South Korea) report MSI 2024-003A fully loaded tanker left port despite a bad weather forecast for the following days. As a precaution, the Master chose a route relatively close to the coast in the event of an emergency.

Some 11 hours after departure, the bilge alarm sounded in the bow thruster room. The OOW considered it to be a malfunction and silenced the alarm. The next morning the bilge alarm in the bow thruster room sounded again. The bilge pump was started for that space, and the alarm soon ceased.

The weather remained relatively fair during the first day of the voyage. By the afternoon of the second day, a strong northeasterly wind was blowing, with waves increasing from four to six metres. In the afternoon of the same day, a 440V low insulation warning alarm was detected in the windlass motor room.

Given the alarms, the Master wanted to check the extent of the problems forward. He altered the tanker’s course to reduce wave impacts at the bow. Crewmembers, including the chief engineer, then went forward and found that there was about one metre of water inside the windlass motor room. The windlass motor room was emptied of seawater using the general service pump and portable air pumps, but the operation was hampered by the ship’s heaving and rolling.

The Master checked the cargo stowage programme on the vessel’s loading computer (Loadcom) to determine the tanker’s safety and seaworthiness in the event of a flooded windlass motor room. The result appeared good, so he decided to continue sailing to the destination port. The next morning, the Master again turned the vessel away from the wind to permit a check in the windlass motor room. There was once again water in the compartment, and the level had reached the top of the entrance stairway. Pumps were employed for about two hours, but were not able to lower the water level.

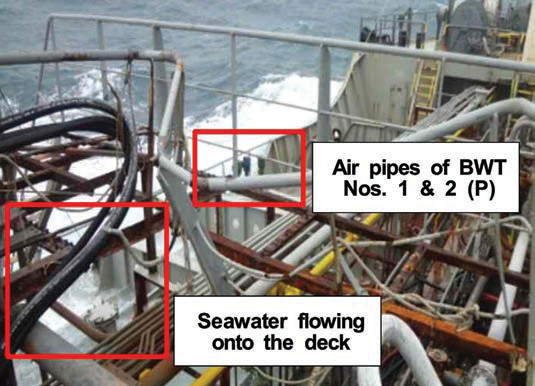

Given the weather forecast and his sailing experience in the area, the Master determined that the weather would improve so he resumed sailing toward the destination port. Later that day the vessel heeled a few degrees to port. Some hours later, the vessel was heeling five to seven degrees to port. It was later posited that port side ballast tanks one and two were taking water due to damaged air pipes caused by the continuous blue water on deck.

To correct the heeling, ballast water was loaded into the ballast water tank on the starboard side, but this did not bring the vessel upright. The vessel was now dangerously overloaded and lacked sufficient reserve buoyancy. The Master then attempted to alter the tanker’s course over a three-hour period with varying success. With the tanker now heeled to port and with negative trim, and given the wind and waves, the manoeuvres did not have the desired effect.

Finally, at 2:40 the following morning, it was decided to abandon ship. A distress signal was sent and a rescue helicopter arrived on scene about 2.5 hours later. Other rescue resources followed, and all crew were recovered. The tanker capsized and sank about six hours later. All crewmembers were rescued, but the chief officer died while being transported to hospital.

The investigation determined from witness testimony and the salvaged vessel, among other things, that the sequence of flooding was as follows: as the weather conditions worsened seawater constantly washed over the forecastle. The seawater inundating the forecastle deck flowed into the chain locker through the spurling pipe, which was not plugged. When the chain locker was full, it flowed through the opened chain locker hatch into the motor room and from there through the open door into the bow thruster room.

Additionally, the investigation found that the three flooded areas (windlass motor room, the bow thruster room, and the chain locker) are excluded from the vessel’s Loadcom program. The simulation conducted by the Master earlier in the voyage to determine the vessel’s seaworthiness was mistaken and gave a false sense of security.

Lessons learned

- It is best practice to plug spurling pipes prior to bad weather and keep chain locker access hatches closed and dogged.

- Ensure your vessel is 100% seaworthy – battened down doors and hatches for all seas.

- Know your ship and the tools available to you, among others the load computer.