202244 Drifting 'give-way' vessel collides with fishing vessel

As edited from TAIC (New Zealand) report MO-2021-203

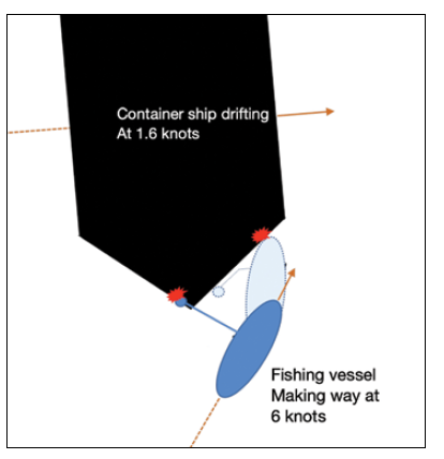

container ship under way was stopped and drifting at sea due to port congestion at the next destination. The OOW was supported by another crewmember as lookout. The vessel was drifting sideways towards the east under the influence of the westerly wind. At 03:10 the lookout reported spotting a small vessel on the radar 6 to 7 nm away and fine on the starboard bow. About 13 minutes later, this target now 3.8nm away, was plotted by the lookout.

At 03:30, the lookout operating the radar reported to the OOW, who was occupied with other tasks, that the target was showing a small CPA. The OOW was not concerned; he assumed, correctly, that the target was a fishing vessel. His expectation, although flawed, was that fishing vessels usually altered course and would keep out of the way, especially as the ship was drifting. Meanwhile the lookout was now using a red laser pointer directed at the fishing vessel to warn its crew of their presence.

At 03:50 the OOW became concerned that the fishing vessel was getting too close and did not appear to be altering course. At 03:55 a relief OOW arrived on the bridge and spent a few minutes familiarising himself with the ship’s situation. He then went to the electrical equipment room behind the bridge with the OOW on duty to investigate a water leak that had developed there during the night.

About three minutes later, both officers were back on the bridge. The relieving OOW asked about the fishing vessel, which was now 0.5nm away and still closing. They soon lost sight of the fishing vessel in the blind sector ahead of the ship caused by the container stow. At this distance the ship’s radar lost definition of the target and any displayed data became unreliable. Very soon after, the fishing vessel made contact with the container ship, but the bridge crew later recounted that they did not see, hear or feel the collision. The lookout was sent forward with a radio to investigate, while each officer went to one of the two bridge wings in an attempt to see what was occurring at the bow. At about 04:05 the fishing vessel emerged from the container vessel’s port bow and remained in the vicinity for about 10 minutes. The bridge team made no attempt to contact the fishing vessel, nothing was recorded in the bridge logbook and the Master was not informed.

The fishing vessel had crossed the container vessel’s bow with the narrowest of margins; so close that the stabiliser arm collided with the stem of the ship’s bow. The fishing vessel then pivoted around the stabiliser arm and its port bow collided under the flare of the container vessel’s port bow near the anchor. Still on autopilot, and with its engine still driving ahead, the fishing vessel slowly scraped along the container vessel’s hull as it rose and fell with the waves.

The fishing skipper, who had left the wheelhouse for other tasks, arrived and put the engine in reverse, backing away from the container ship. It soon became apparent that the watertight integrity of the hull was intact. The skipper then attempted to contact the container vessel by VHF radio, but because the communication antenna had been damaged this was unsuccessful. The crew then severed the fishing line and departed the scene, heading for port.

The investigation found that, although drifting, the container vessel was nevertheless considered to be a power-driven vessel underway and was therefore required to follow the Colregs and take the appropriate action to avoid a collision, which it did not. The container vessel’s bridge crew had detected and were plotting the progress of the fishing vessel on their radar. They had correctly identified the target as a crossing vessel, but it did not occur to them that their vessel was the give way

vessel.

The bridge crew were working on two false assumptions.

- First, that because their vessel was drifting this put the onus on other vessels underway to avoid their ship.

- Secondly, because the target was probably a fishing vessel, it would give way to them by virtue of their size.

The fishing vessel’s skipper made no attempt to sight the container vessel after noticing it on the radar at 4nm distance because he was occupied with other tasks elsewhere on the vessel – no one was in the wheelhouse.

Another important finding of the investigation was that there is mounting evidence showing a compromise in crewing levels aimed at keeping small fishing vessel operations economically viable. This in turn is resulting in fishing crews either not achieving full compliance with national and international legislation or operating when fatigued. Either way, the result will be a higher risk of these vessels being involved in collisions or groundings.

Lessons learned

- All vessels have a part to play in preventing collisions at sea, regardless of whether they are the stand-on or give-way vessel.

- Making assumptions about the intentions of other vessels based on false or scanty information is high risk, which will inevitably contribute to collisions at sea.

- When drifting, you are still a vessel underway and may need to manoeuvre as per the Colregs. Keep your engines at the appropriate level of readiness given the local circumstances.

- Should you wish to attract the attention of another vessel, do not use a laser pointer. Try the Aldis lamp, the ship’s searchlight or the ship’s horn (at least 5 short blasts).