202234 Sleep inertia can be costly

As edited from NTSB (USA) report MIR 22/09

A tug was pushing two steel tank barges loaded with naphtha on an inland waterway. The Master had been at the con/helm for several hours before retiring to his cabin for some rest. About 4.5 hours later, a little after 0500, the Master awoke and proceeded to the wheelhouse to assume the watch, even though his watch normally started at 0600.

The tow was approaching the eastern end of a lock when the Master entered the wheelhouse. The officer offered to take the tow through the lock before turning over the watch, but the captain declined and took the con/helm about five minutes before manoeuvring the tow into the lock. The officer informed the Master that he was having trouble communicating via handheld radio with the deckhand, who was stationed on the lead barge.

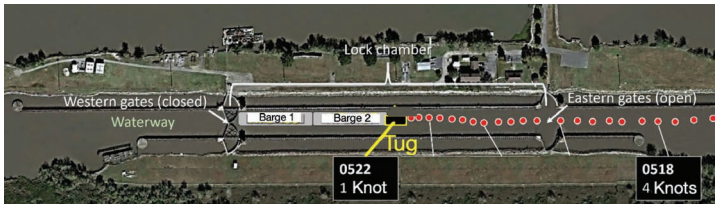

The Master reduced speed on the engines, keeping them ‘in clutch’ ahead to provide steering control as the tow neared the long wall on the north side of the lock. The Master’s expectation, from experience, was that they would stop and secure in the lock with the bow of the lead barge about 15 metres from the closed gates ahead. However, on this morning, he was not consistently receiving distance reports from the deckhand because of ongoing trouble with their handheld radios.

As the Master was manoeuvring the tow in the lock, the GPS feed to his electronic chart system (ECS) failed, denying him his primary source of speed indication. In the darkness, he had to judge the speed of the tow by watching the illuminated lock wall through his side windows and the lock gates through his forward windows.

With the tug and barges now at a speed of about two knots, the Master received a distance report from the deckhand and, realising they were close to the front of the lock, put the engines to full astern. The tow continued to slow but was still making about one knot when the starboard bow of the forward barge (1 in picture) struck the closed western lock gate.

The official investigation found that the Master’s performance and decision making were probably negatively affected by sleep inertia. Sleep inertia can be a factor for 30 minutes or more after waking, especially in demanding situations that require high levels of attention and cognitive demand. Further, waking during a circadian low, such as in this case at 5am, and partial sleep deprivation, can amplify the effects of sleep inertia.

Lessons learned

- The company operations manual required that a change of watch was not to occur during ‘a critical move’. Examples included operations involving ‘bridges, locks, and docking operations’. The requirement is one of common sense and, in this case, does seem fully justified.

- Fatigue has many negative effects on performance and is notoriously hard to objectively assess by its victims. Sleep inertia is a silent companion to fatigue and mariners would be well served to be aware of its existence.

Editor’s note: Accidents rarely if ever happen because of one unsafe condition or unsafe act. This accident is an excellent and clear example of this theory. The Master was possibly under the influence of sleep inertia, but several other factors had to conspire to bring about the end result. It was dark, so visual perception is reduced as compared to full daylight. As has been mentioned before in MARS, darkness changes everything. Additionally, communication with the deckhand forward was problematic and the GPS speed input failed at just the wrong time.