202207 Collision with a fishing vessel while outbound from a port

As edited from official TAIC report (New Zealand) MO-2020-201

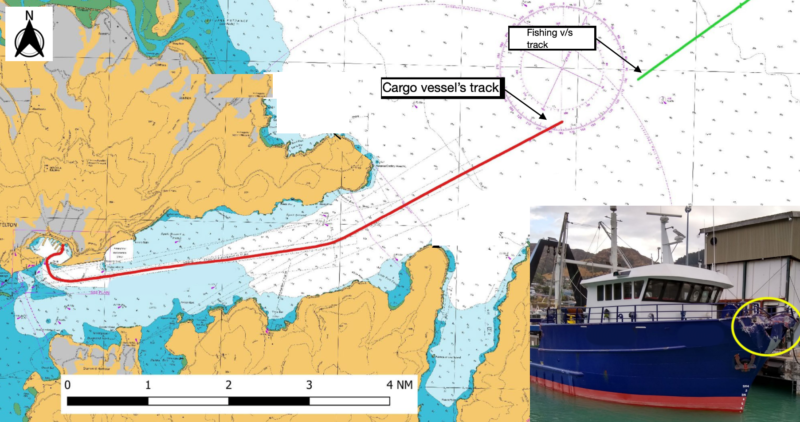

A cargo vessel was leaving port under pilotage, in darkness but with good visibility. The bridge team comprised the pilot who had the con, the Master, OOW and a helmsman. Also on the bridge were three representatives of the vessel charterer who were making an observation trip to the next port.

As the vessel exited the port, the pilot handed the conduct of the vessel to the Master in preparation for disembarking. There was no discussion about traffic in the area during the handover, and the bridge team had not noticed the presence of an inbound fishing vessel some 5 nm ahead. The OOW accompanied the pilot to the main deck and observed as the pilot boarded the pilot launch.

When the OOW returned to the wheelhouse the Master was in discussion with the three passengers. The OOW then observed a small vessel fine on the port bow. Viewed through binoculars, both the port and the starboard navigation lights were visible. The OOW informed the Master of the small vessel’s presence.

At this point, the fishing vessel was approximately 3.5 nm away, but it was not yet showing as a target on the radars because they were still set to the 3 and 0.75 nm range scales used to exit the port. The fishing vessel had a speed over ground (SOG) of about 7.8 knots. The SOG of the outbound cargo vessel was 8.2 knots. As the cargo vessel came clear of the port channel, the Master ordered the engine speed to be increased, giving a new SOG of about 11.8 knots. At this point, the vessels were about 10 minutes apart.

A few minutes later, the OOW interrupted the discussion between the Master and the passengers to inform the Master of the developing situation with the fishing vessel. The Master acknowledged the OOW and continued the conversation with the passengers. The fishing vessel was now 1.5 nm away and on an apparent collision course, yet neither vessel had altered course.

The OOW now informed the Master that the fishing vessel’s CPA would be 0.047 nm. Soon after this, he told the Master that the fishing vessel’s Course Over Ground (COG) was 230°. The Master first confirmed with the helmsman that own ship’s course was 060°, then ordered the helmsman to alter course 10 degrees to starboard to avoid a collision. Soon after, the OOW informed the Master that the bow crossing range was 0.089 nm. At this point the Master ordered hard starboard and sounded one continuous long blast on the vessel’s whistle. Within seconds the cargo vessel and the fishing vessel collided.

The fishing vessel’s bridge was manned by a lone watchkeeper who was not sufficiently familiar with the Colregs to stand a watch. He had left the bridge about one minute before the collision to wake the Master, unaware that they were running into danger. As the crew and the Master regained the wheelhouse of the fishing vessel they heard the whistle of the approaching cargo vessel. The Master attempted to steer to safety but the two vessels collided shortly afterwards. Only minor injuries were sustained by the Master of the fishing vessel and the vessel sustained bow damage.

The official report found, among others, that;

- The bridge team on board the cargo vessel, both during the pilotage and immediately after the pilotage ended, had low situational awareness of other marine traffic in the vicinity due to distractions (passengers on bridge) and the absence of long-range scanning to obtain an early warning of the risk of collision.

- The sole watchkeeper on board the fishing vessel had low situational awareness of the risk of collision with the cargo vessel because the radar equipment was not used to plot the target’s track. Also, the watchkeeper on board the fishing vessel was not sufficiently familiar with the Colregs to undertake a sole watch.

Lessons learned

- Distractions on the bridge will ALWAYS lead to lower situational awareness. Unnecessary personnel or passengers on the bridge, portable phones, sundry other tasks other than navigation; these will erode your safe navigation.

- Early warning of an impending collision by radar can only be achieved by long range scanning and target acquisition.

A few minutes later, the OOW interrupted the discussion between the Master and the passengers to inform the Master of the developing situation with the fishing vessel. The Master acknowledged the OOW and continued the conversation with the passengers. The fishing vessel

was now 1.5 nm away and on an apparent collision course, yet neither vessel had altered course.

The OOW now informed the Master that the fishing vessel’s CPA would be 0.047 nm. Soon after this, he told the Master that the fishing vessel’s Course Over Ground (COG) was 230°. The Master first confirmed with the helmsman that own ship’s course was 060°, then ordered the helmsman to alter course 10 degrees to starboard to avoid a collision. Soon after, the OOW informed the Master that the bow crossing range was 0.089 nm. At this point the Master ordered hard starboard and sounded one continuous long blast on the vessel’s whistle. Within seconds the cargo vessel and the fishing vessel collided.

The fishing vessel’s bridge was manned by a lone watchkeeper who was not sufficiently familiar with the Colregs to stand a watch. He had left the bridge about one minute before the collision to wake the Master, unaware that they were running into danger. As the crew and the Master regained the wheelhouse of the fishing vessel they heard the whistle of the approaching cargo vessel. The Master attempted to steer to safety but the two vessels collided shortly afterwards. Only minor injuries were sustained by the Master of the fishing vessel and the vessel sustained bow damage.

The official report found, among others, that;

- The bridge team on board the cargo vessel, both during the pilotage and immediately after the pilotage ended, had low situational awareness of other marine traffic in the vicinity due to distractions (passengers on bridge) and the absence of long-range scanning to obtain an early warning of the risk of collision.

- The sole watchkeeper on board the fishing vessel had low situational awareness of the risk of collision with the cargo vessel because the radar equipment was not used to plot the target’s track. Also, the watchkeeper on board the fishing vessel was not sufficiently familiar with the Colregs to undertake a sole watch.

Lessons learned

- Distractions on the bridge will ALWAYS lead to lower situational awareness. Unnecessary personnel or passengers on the bridge, portable phones, sundry other tasks other than navigation; these will erode your safe navigation.

- Early warning of an impending collision by radar can only be achieved by long range scanning and target acquisition.

Fishing for lessons learned – Conclusion

Collisions between commercial ships and small vessels are unfortunately still a relatively common occurrence. Statistics from an Australian study (1990 to 2017) revealed 63 reported collisions of this type. The occurrences that were investigated found that a proper and effective lookout and taking early avoiding action in accordance with the Colregs could have prevented those collisions in almost every instance.

It is worth quoting an insight published in one Australian report of such an occurrence (ATSB/333-MO-2017-007):

“Human performance aspects that are relevant to some of these collisions include expectancy and confirmation bias. Expectations are based on past experience and other sources of information, and they strongly influence where a person will search for information, what they will search for and their ability to notice and recognise a target or relevant aspect of a situation (Wickens and McCarley 2008). If the expectations are incorrect, then a person will be less likely to detect the target or a relevant aspect of the target (such as the heading or speed).

People generally seek information that confirms or supports their hypotheses or beliefs, and either discount or do not seek information that contradicts those hypotheses or beliefs. When the available information is ambiguous, it will generally be interpreted as supporting the hypothesis. This confirmation bias is an inherent aspect of human decision-making and has been demonstrated to occur in a wide range

of contexts (Wickens and Hollands 2000).

If an assessment of another vessel’s heading and speed is based on limited or incomplete information, there is a significant likelihood it will

be incorrect. However, aspects such as expectancy and confirmation bias mean an initial incorrect assessment may not be effectively identified and corrected.

You may also like:

The drive for fishing vessel safety management. A Seafarer's Charity initiative