201756 Unconventional design contributes to loss of situational awareness

Edited from UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch official report 3/2017

In darkness and under pilotage a car carrier was outbound in a river estuary behind another outbound vessel. The car carrier was to the north of the channel and of the intended track. The pilot informed the Master that he would try and manoeuvre the ship further to the south. At the time an approaching vessel, an inbound ro-ro ferry, was in clear sight. The pilot of the car carrier informed the Master that they would pass the ro-ro port to port.

When the two vessels were 2.8nm apart the car carrier was making 12kts and the ro-ro near 16kts; they would meet in six minutes. The ro-ro’s Master and second officer were concerned that the car carrier remained on the northern side of the channel and did not appear to be altering course to the south. The VTS watch manager was also concerned; both he and the ro-ro’s second officer called the car carrier in quick succession on VHF to inquire as to its intentions.

As the distance between the two vessels diminished, now at 0.97nm, the ro-ro continued on a heading of 295° and the car carrier’s pilot ordered to steer 115°.

The ro-ro’s Master decided to reduce speed and put the telegraph to ‘half ahead’, which gave a speed through the water of approximately 9kts. At about the same time the car carrier’s pilot ordered ‘starboard 20’. As the car carrier’s heading reached 125°, the pilot ordered midships, then 135°. Accordingly, the helmsman arrested the vessel’s swing to starboard to steady the vessel as ordered. The car carrier’s Master expressed concern over the developing situation and the pilot explained to him that both vessels were experiencing drift.

Shortly thereafter the ro-ro’s bridge team realised that the car carrier was not turning to starboard as quickly as they expected and that emergency measures were needed. Full starboard helm was applied and the engine was set to full astern. Very shortly after, the car carrier’s Master also realised emergency action was necessary – he shouted ‘Go to starboard’, followed by ‘Midships’ and then ‘Hard to port’. Fourteen seconds later the two vessels collided port bow to port bow on headings of 288° and 163° respectively.

The official investigation found, among other things, that:

- The collision stemmed from the car carrier being set to the northern side of the channel by the wind and the tidal stream, followed by the distortion of its pilot’s spatial awareness due to a ‘relative motion illusion’.

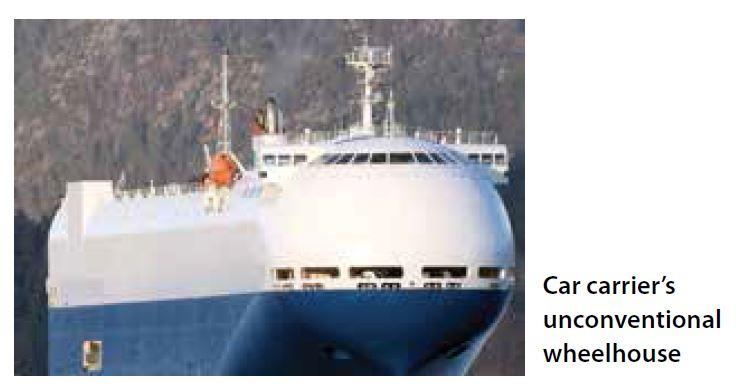

- The car carrier pilot’s view from the window he was using was 33° off the vessel’s centreline axis, which contributed to the relative motion illusion. It deceived him into thinking that his view was the same as the vessel’s direction of travel.

- The inward slope of the bridge window removed all objects from the car carrier pilot’s peripheral vision. There were no forward visual clues such as a bow tip, and the illusion would have been compelling.

- The car carrier’s bridge team did not challenge the pilot’s actions in a timely manner despite concerns being expressed by the oncoming ro-ro vessel’s team and the VTS.

- The car carrier’s bridge team was over-reliant on the pilot; their lack of effective monitoring of the vessel’s progress was evidence of ineffective bridge resource management.

Lessons learned

- When in pilotage waters do your own navigating to validate the pilot’s actions and to keep your situational awareness at its peak.

- Keep the pilot appraised of any deviations from the planned track and the vessel’s actual track.

- If your vessel has special ergonomic characteristics or particular manoeuvring considerations, make sure the pilot is well informed of these points and that they are taking them into consideration while under pilotage.