201417 Stretcher past its limit

Edited from Germany’s Bureau of Maritime Casualty Investigation (BSU) report no. 422

Prior to undertaking the berthing manoeuvre of a car carrier, the crew of the aft assisting tug discussed the particular hazards of the job as well as the use of personal protective equipment. The towing gear was visually inspected and no deficiencies were found. Environmental conditions at the time were good; there was hardly any swell or wind.

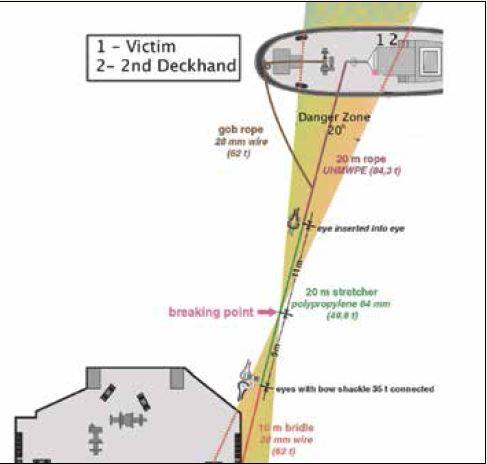

The towline system consisted of three parts: a 10m bridle to the assisted ship (28mm cable rated to 62 t), connected with a round pin anchor shackle, then the 20m stretcher (initially reported to be polypropylene, 64mm rated to 49.8 t), and 20m of ultra high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) rope (rated to 84.3 t), as well as a 28mm tricing cable (rated to 62 t), which was attached to the towline using a round pin anchor shackle and controlled by means of a tricing winch.

The tug made fast aft and commenced operations. Following the pilot’s instructions, they were to pull at an angle of 90°. Everything seemed to be going well when suddenly the stretcher parted and struck one of the deckhands, who was standing in front of the port side companionway. Standing beside the victim, the second deckhand managed to avoid injury. The victim was given initial medical aid and transferred to the hospital where he was diagnosed with severe injuries to his legs. The victim was experienced and had worked on the tug for the past 11 years.

As can be seen in the diagram, the deckhands were within the snap back zone. A parted towline snaps back faster than the speed of sound. This means that the break had already occurred before the bang was heard on the aft deck; the deckhands could not move to safety in time if they were still within the danger area. While the best protection is located in the superstructure, the Master and chief mate were already on station there leaving no room for the two deckhands. The procedures of the owner’s quality management system do not define safety areas for the crew. Although the deckhand’s safety area beside the companionway was apparently tried and tested at an earlier time, an analysis shows that the only possible safety area on the deck of an aft tug would be the forward edge of the bridge. Yet this is impractical on this tug as the trigger for the slip device cannot be accessed from that location.

As can be seen in the diagram, the deckhands were within the snap back zone. A parted towline snaps back faster than the speed of sound. This means that the break had already occurred before the bang was heard on the aft deck; the deckhands could not move to safety in time if they were still within the danger area. While the best protection is located in the superstructure, the Master and chief mate were already on station there leaving no room for the two deckhands. The procedures of the owner’s quality management system do not define safety areas for the crew. Although the deckhand’s safety area beside the companionway was apparently tried and tested at an earlier time, an analysis shows that the only possible safety area on the deck of an aft tug would be the forward edge of the bridge. Yet this is impractical on this tug as the trigger for the slip device cannot be accessed from that location.

Some of the findings of the official report were:

* The material used for the fabrication of the stretcher was of low quality. Polypropylene split film of this type is normally used for mooring lines. The rope was manufactured and delivered without any of the ‘tracer’ threads that identify the company or the standard.

* The stretcher should never be the weakest component of the towing connection. Since a failure of the stretcher is virtually a worst case scenario, this element is normally oversized by 1.5 times the maximum tensile strength of the other connecting components, which themselves are usually set at two to three times the bollard pull of the tug.

* Best practice dictates that the length of the stretcher should be no less than 5m and no more than 10m for port towing connections. Also, only fairlead shackles should be used for connecting individual components of the towing gear. Both of these best practices were ignored in the present case.

* Prior to being used in this incident, 73 of the total of 456 fibres of the stretcher were already completely or partially frayed. The failure of the stretcher was primarily caused by this pre-existing damage.

Editor’s note: Accidents are very rarely, if ever, the result of a single factor. This accident is a prime example of that rule of thumb. Although the stretcher was of inadequate quality and was already damaged before use, a series of less than adequate practices and failed risk analysis (safety area of crew on stern) also combined to aggravate the consequences of this accident.