200862 Lamellar tear in ballast hold

A 10-month-old capesize bulk carrier had done only four ballast voyages since delivery. During these voyages, there was evidence of seepage of ballast water from ballast hold no. 3 into cargo hold no. 4. The location of the 'leak' appeared to be at the connection between the corrugated bulkhead between holds 3 and 4 and the lower stool, centred about four metres to port of the centre-line. Dye penetrant tests did not reveal a crack in the weld, nevertheless, the management instructed the ship's staff to gouge the weld for about two – three metres and reweld the connection.

The ship's stability manual specifically required the filling of the ballast hold before proceeding to sea without cargo and prohibited its deballasting during navigation. Furthermore, filling and emptying of ballast in this hold required a minimum of eight to 10 hours. This precluded the repair operations from being carried out during the ballast voyage. Hence, access to this area was only possible for about two or three hours every voyage, towards the end of cargo discharge in holds three and four, when stevedores would be involved in clearing out the remnants of the cargo and ship's staff would be cleaning and preparing hold no. 3 for ballasting.

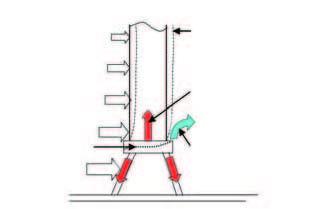

1. Side elevation of typical ballast hold showing how lamellar tear is caused

1. Side elevation of typical ballast hold showing how lamellar tear is caused

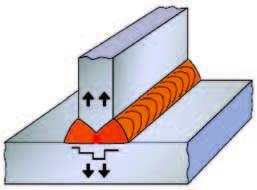

2. Close up of typical fillet welded joint at connection of hold transverse bulkhead and lower stool top plate

2. Close up of typical fillet welded joint at connection of hold transverse bulkhead and lower stool top plate

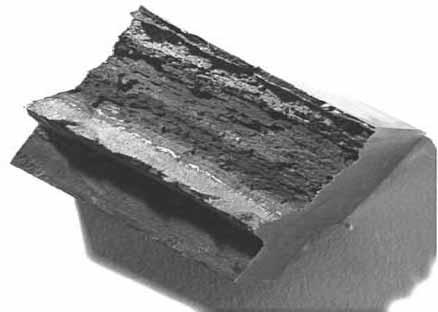

3. Cross-section of a typical lamellar tear showing ‘porous’ strata

3. Cross-section of a typical lamellar tear showing ‘porous’ strataDuring the first change of master, with the ship about six months old, the relieving master was verbally informed of the situation and told that two previous attempts in gouging and rewelding in the location had failed to rectify the defect. The management advised the new master to continue with the same repair strategy of gouging and rewelding the connection.

Overcoming difficulties in obtaining hot work permits at the next two discharge terminals, the new master arranged for two more repeats of gouging and rewelding, this time, stationing an observer inside the lower stool space before and during the process. No trace of water was seen in this space but after rewelding and ballasting hold no. 3, water was again observed to leak into hold no. 4.

As far as the ship's staff could discern, the company had not informed the flag administration or the classification society of this defect. Furthermore, despite the defect apparently having been noticed within a few months of delivery, there was also no evidence on board of the managers having submitted a guarantee claim against the shipbuilder for this defect.

While the last repair attempt was in progress in a discharge port, a port-state control team boarded for the ship's maiden inspection in that memorandum region. The officers became curious, seeing the electric welding cable leading from the engine room along the upper deck, and followed it to the hot work site in hold no. 4. On learning from the ship's staff about the defect, they informed the classification society. A class surveyor soon boarded and after a brief inspection, diagnosed the problem as a lamellar tear in the lower stool plate and imposed a condition of class. He expressed his strong disapproval of the repair attempts by ship's staff without consulting class.

Unfortunately, in the eyes of the misguided management, the master was declared to be 'inefficient' in not getting the defect rectified and, after being 'reprimanded' for informing class and also 'accepting' a condition of class, was relieved of his command at the next port.

Lessons learned

A lamellar tear must be suspected whenever there is leak through a plate and traditional methods do not detect a crack. Ultrasound is more reliable than x-rays in their detection.

The tear normally exists within the thickness of the plate and so will not normally be visible on the surface.

Locations where a plate is subject to high tensile forces across the thickness (not along the longitudinal axis) are particularly prone to lamellar tears. Hence, fillet joints are susceptible, whereas butt joints never have this problem.

The problem may be exacerbated by poor material, design, construction, increased plate thickness.

In a large bulk carrier's ballast hold, the head of water exerts a very large force on only one side of the bulkhead, and causes a tensile force across the thickness of the lower stool top plate. This can only be countered by adequate scantlings of the bulkhead and proper design of its joints.

The administration and classification society must be informed immediately whenever a structural defect is discovered and repairs must be only carried out with and under class supervision.

Solas and Marpol regulations require masters to inform the nearest coastal and port state authorities of any defect on the vessel that may affect her safety, structural integrity, navigation and impact on the environment.