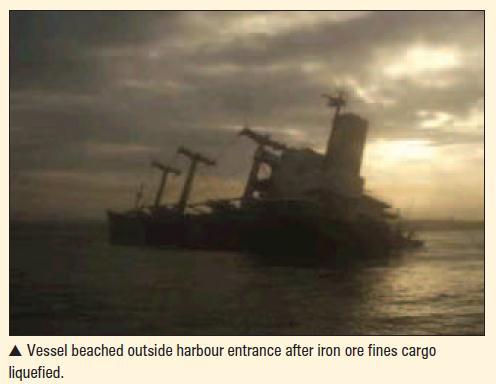

200842 Beaching after iron ore liquefaction

Source: Skuld Loss Prevention, issue 6, November 2007

A dry cargo ship loaded 20,000 MT iron ore fines. After sailing and when only a few nautical miles outside the port, the vessel started to develop a list. The list continued to increase and the captain intentionally ran the ship aground (beached it) to avoid capsizing.

A dry cargo ship loaded 20,000 MT iron ore fines. After sailing and when only a few nautical miles outside the port, the vessel started to develop a list. The list continued to increase and the captain intentionally ran the ship aground (beached it) to avoid capsizing.Consequences of incident

Costly salvage operation;

Bottom and hull damage;

Six weeks off hire.

Root cause/contributory factors

The ore at the port concerned is generally saturated with water when extracted from the mine;

The ore was stored in the open for a prolonged period during the rainy season;

The shipper failed to provide certificates showing moisture content (MC) and transportable moisture limit (TML); meanwhile the ship's staff did not seem to have been aware of the unusual wetness of the cargo and the requirements under the BC Code;

The high moisture content, combined with the main engine's vibrations, caused the cargo to liquefy. This resulted in the ship nearly capsizing before being successfully beached by the Master.

Lessons learnt

Every dry bulk cargo composed predominantly of fines and small particles, and that contains or is suspected to contain moisture, should be properly tested for MC and TML prior to loading.

The BC Code certification requirements apply to all cargoes which may liquefy regardless of whether or not the cargo is specifically identified as posing a liquefaction risk. Never assume there is no risk of liquefaction simply because a cargo is not identified as Group A in the BC Code.

When considering the carriage of Group A cargoes and other cargoes that have a liquefaction risk, owners should seek assurance from charterers that the certificates of moisture content and TML will be made available prior to shipment.

If these certificates are not available at the load port, the master should consider refusing the cargo and immediately notify the owners, who in turn should contact their P&I club for advice.

Any certificates provided should be checked to ensure that they are from an independent and reliable source. Certificates issued by the mining company may be unreliable.

Where possible, the ship's staff should examine the condition of the cargo closely before it is loaded; they should monitor its condition closely throughout loading and whenever it is brought alongside the vessel. Even when the cargo appears to be dry, it may still contain moisture in excess of TML; but if it appears clearly wet, or is stored in open conditions in rainy weather, experience indicates that the moisture content may well be above TML.

Even if the cargo sample passes the 'can test' described in Section 8.3 of the BC Code (no free moisture or fluid condition is seen), it does not necessarily mean that the cargo is safe for shipment, and an independent test may still be prudent. However, if free moisture is seen at the end of a can test, further testing, at least, must be done before deciding on loading the cargo and its effect on the safety of the ship.

Shipmasters and owners should closely follow the recommendations contained in the BC Code in all circumstances.

The main areas from where such wet ores are exported are India, China, Philippines, Indonesia, New Caledonia and smaller ports in the Asia-Pacific region but mariners are warned to exercise caution with such cargoes irrespective of port of shipment.

If in any doubt, mariners should contact the nearest P&I club correspondent for advice.

Editor's note: In the latest edition of the BC Code (2004), there is no direct reference to iron ore fines and the possibility of liquefaction may not be readily obvious. It is suggested that in the next revision of the Code, separate entries for all ore 'fines' be inserted in the individual schedule of bulk cargoes, drawing the attention of users to the liquefaction hazards of such consignments and the factors that are likely to exacerbate them.