Introduction

This part of the guide offers plain language explanations of the measures ports and terminals may adopt to address the risk presented by excessive time pressure on seafarers and port workers alike. This part of the Ports/Terminals guide focuses specifically on due diligence. The guidelines describe measures that may be taken to mitigate the associated risk and may inform the due diligence associated with port and/or terminal nomination within the scope of a ‘safe port warranty’.

Due Diligence

Due diligence is a process that involves a risk and compliance check; conducting an investigation, review, or audit to verify facts and information about a particular subject. Put simply, due diligence means one party acquiring knowledge before entering into any agreement or contract with another (a counterparty), to establish as far as reasonably practicable that the engagement will not subsequently present an unacceptable risk. Many shipping companies routinely perform due diligence on new and existing customers, for example, to satisfy themselves that they are not engaging with an entity subject to sanction by the United States – to do so would be potentially catastrophic.

When and why?

What form of due diligence is appropriate depends on the specific situation, business transactions and the level or scale of risk. Again using sanctions as an example, basic due diligence (BDD)could be in the form of a non-rigorous review of information or other public domain sources such as screening against key sanctions lists, which may be sufficient for a EU-based counterparty that is unlikely to be involved in nefarious dealings with North Korea or Iran. Conversely, if the counterparty is based in a regime with less robust controls on finance and exports, enhanced due diligence (EDD)in the form of the identification and screening of the ultimate beneficial owners and the completion of declarations of compliance may be considered prudent.

Beyond that, should the counterparty be a diverse multinational embracing activities in states with a large number of entities and / or individuals subject to sanction, then full robust integrity due diligence (IDD) may be called for in the form of site visits, third party investigations and / or engagement of legal counsel or other specialist for fact finding.

Important to stress that there is no legal obligation on a shipping company or charterer to perform due diligence on their counterparties, including ports and terminals. A matter for the relevant management to determine as a function of its risk appetite. Bearing in mind the time required and costs involved, performing due diligence on a port or terminal prior to nomination may be considered an unnecessary burden.

Nevertheless, with increasing societal pressure on the shipping sector to deliver on the principles of ESG6 establishing a consistently robust risk and compliance check on a port and / or terminal through due diligence has the potential to make an organization shine in the eyes of investors, financers and the attestation bodies that increasingly benchmark the industry, and may address hitherto largely unconsidered risk associated with port operations.

Port operations

This section will detail the different port operation processes and how due diligence can be promoted to mitigate risks and offer an overall safer environment for seafarers and port workers alike.

Port Call Process

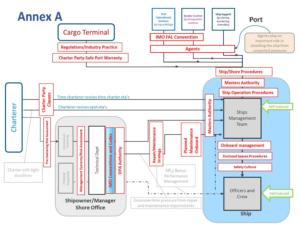

For every port call many different operations must be performed at just the right time, the process an important element in safe and efficient shipping broadly consisting of two phases: contractual and operational.

The contractual phase includes the hiring (charter) of the ship together with the port / terminal services required, to fulfil the needs of the cargo owner (shipper) seeking to move goods from one location to another.

The operational phase includes the planning and delivery of all related activities through the various phases of port operations as summarised in the figure below.

Said operations involve a substantial number of shore-based actors. To enter port, authority approval must be secured; typically the service of pilots and tugs secured t and stevedores engaged and thereafter overseen to handle cargo operations without compromising the safety of the ship, or themselved.

In addition, the ship must deal with, among others, waste disposal contractors, chandlers and bunker suppliers, and in all likelihood the representatives of cargo interests all demanding the attention of ship’s staff, particularly the master and senior officers, time that ideally should be prioritized for rest[1].

[1] Minimum hours of rest as determined in the MLC and STW.

Enclosed spaces

Serious risks to health can arise from entering or working in confined spaces. Although there are potential confined spaces in warehouses and elsewhere in port areas, incidents during port work are most likely to occur on board ship, particularly when port workers enter holds. Unfortunately, as reported by the International Bulk Terminals Association (IBTA)[1] among others, such incidents involving port workers occur too frequently and often involve fatalities.

The term “confined space” generally means an area that is totally enclosed. However, this does not mean airtight, nor does it refer just to a small space. While small spaces can be confined and potentially dangerous to enter, the risks also apply to much larger spaces. For example, a ship’s hold may be a large void but must be treated as a confined space and the atmosphere in it, including the access ways to the hold, may well be hazardous. Special precautions should be taken and the enclosed space entry procedures established by the ship strictly observed where there is a risk of an unsafe atmosphere particularly where:

• The cargo has been fumigated.

• The cargo has oxygen depleting characteristics.

• The cargo is liable to give off flammable or toxic vapours.

[1] Analysis-of-Shipboard-Confined-Space-Accidents-1999-April-2018, IMO Paper CCC 5/INF.12 (United Kingdom and IBTA).

Ship-shore communications

As reflected in the IMO Bulk Load and Unloading (BLU) Manual, effective communication, and the securing of agreement, between ship and port personnel is an essential mechanism for addressing the risk associated with the port process, the exchange of expected and realistic times to complete the tasks associated with the port operational phase make it possible to plan a port call in a smarter and more efficient way while also enhancing safety.

Among other things, prior to commencing cargo operations the master and terminal representative should collectively agree on the time necessary to ensure that checks are undertaken so that cargo spaces and other enclosed spaces are either secured (to prevent entry by port personnel) or persons - not least stevedores - are permitted to enter only after the spaces have been declared safe for entry in accordance with the guidelines developed by the IMO[1].

Further, the master should be satisfied that sufficient time is allowed such that port personnel are made fully aware of the ship’s policies and procedures established within the scope of the International Safety Management (ISM) Code, for example, through training toolboxes if not previously assured in some way at the time of port nomination.

The time allocated to the above should not be compromised or otherwise constrained by commercial and other pressures to proceed with haste.

[1] IMO Assembly Resolution A.1050.

Safe port warranty

Many standard form charter parties contain an express warranty or similar contractual obligation on the part of the charterer[1], to the benefit of the ship owner, to ensure the ‘safety’ of the nominated port. Even in the circumstance where such a warranty is not expressly provided for there remains the possibility that such warranty could be implied should a dispute subsequently arise between ship owner and charterer.

Safe port warranty definition

In law, the long-standing definition of a ‘safe port’ is established to be:

| A port will not be safe unless, in the relevant period of time, the particular ship can reach it, use it, and return from it without, in the absence of some abnormal occurrence, being exposed to danger which cannot be avoided by good navigation and seamanship…(Court of Appeal in Leeds Shipping v Société Française Bunge (The EASTERN CITY) [1958]). |

Should disputes arise, thus far the factors taken into account in the determination of the ‘safe port’ obligation established through the charter largely resolve to matters physical.

|

For example, the US Supreme Court ruling on Citgo Asphalt Refining Co. v Frescati Shipping Co., Ltd., the dispute arising from a 2004 oil spill in the Delaware River involving the M/T Athos I striking a submerged 9-ton abandoned anchor on the approach to intended berth, puncturing the hull of vessel and causing 264,000 gallons of heavy crude oil to spill into the river. Finding in favour of the ship owners, the court opined the contract (charter) must be construed as an express warranty of safety, imposing on the charterer an absolute duty to select a safe berth. Which does not preclude consideration of non-physical dangers to a ship and crew in a safe port warranty dispute like those now being taken into account in seaworthiness disputes. Indeed, in its ruling, the Supreme Court reminded the parties that vessel Masters have an "implicit" right to refuse entry to a port should they find it unsafe, for any reason, and that refusal requires charterers to pay the associated cost. |

In response to the case referenced above and similar, some charter forms now expressly qualify the obligation to nominate a safe port to one of due diligence. In these instances, the charterers’ obligation is merely to take reasonable care to establish that the nominated port is safe, but what does this require in practice; what is ‘due diligence’ in the context of establishing whether a port is safe.

[1] The ‘charterer’ is the entity that contracts (hires) the ship on behalf of the cargo owner (the ‘shipper’). These may be one and the same entity.

What is ‘due diligence’ in the context of establishing whether a port is ‘safe’?

There is no simple answer; whether a charterer has sufficiently discharged its due diligence duty is a highly fact intensive and case-by-case determination. Nevertheless, notwithstanding the complexity of the problem, leading counsel recommends charterers should methodically approach their due diligence obligations by developing vetting practices that keep abreast with industry standards and evolving case law and that are consistent with the company's overall approach to HSE issues but also customized to the unique risks of a particular terminal.[1] From the perspective of time pressure, the matters to address in this vetting process are considered below.

Has the Port Embraced Digitalisation?

Issue

As introduced previously, port operations necessarily involve bureaucracy. They must secure the permit (written, electronic or informal) to allow a certain process to be performed.

| For example bunkering, or handling the documentation associated with the cargo; bills of lading etc. |

Depending on the circumstance, port-related bureaucracy can have both a direct and indirect impact on time pressure. Each actor has their own deadlines and likely views they should have the highest priority, be it the cargo owners seeking to secure clearance to commence cargo operations through to the chandelier with a rapidly deteriorating stock of perishable goods, each requiring ‘time’ to complete their task.

As discussed below, traditionally port bureaucracy was handled by the ship’s agent. Moreover, to the extent that the master was required to be directly involved with port and / or cargo interests, he or she would be assisted by otherwise ‘spare crew’, for example the purser.

However, with improved ship-shore communications, some may consider the services of an agent to be an unnecessary luxury, compounded by the near extinction of the purser and other ‘spares’ to a ship to offer the master support to deal with the bureaucracy especially where this remains paper-based.

Finally, bureaucracy can be associated with nefarious practice, i.e., corruption. Direct access to the master and other senior staff, on the pretext of demanding completion of paperwork, seen to improve the likelihood of securing financial or other benefits from the ship.

Reducing, ideally removing the need for external actors to access the ship in port therefore has a direct impact on reducing the potential for corruption, as is achieved through digitalisation.

Regulation and Standards

The main objectives of the IMO Facilitation Convention (FAL) are to prevent unnecessary delays in maritime traffic, to aid co-operation and to secure the highest practicable degree of uniformity in formalities and other procedures associated with maritime traffic, including those associated with port operations.

Effective April 8, 2019, FAL requires Contracting Governments to establish a protocol for an electronic information exchange between ship and port without the need for personnel to demand the personal attention, and time, of the master.

Further, at the fortieth session of the Facilitation Committee (FAL.40), the IMO adopted resolution FAL.12(40) to amend FAL requiring the establishment of systems for the electronic exchange of information associated with the port process through a "single window" compliant with the guidelines of the organisation(1).

Presently a recommendation, the requirement for each port to establish – or have access to - a single window for port-ship data exchange, and the completion of all documentation related to any aspect of the port process, is anticipated to be mandated from 1 January 2024 (2).

Compliance Best Practice

|

Level 0 |

No provision for electronic submission of documents related to the port process; actors seek and require unfettered direct access to the master and/or requirement on ships to engage an agent.

|

|

Level 1 |

Key regulatory port clearance documents (IMO FAL series) accepted electronically, however actors generally seek direct access to the master; local port regulation requires engagement of a ship’s agent.

|

|

Level 2

|

Single window established to handle submission of essential regulatory and port operational documents, for example pilot booking, but not fully compliance with IMO standards, some actors, e.g., cargo interests, continue to demand access to master, ships agents subject to licensing by the port. |

|

Level 3 |

Single-window established compliant with IMO standards, all port regulatory, operations and cargo-related information exchange facilitated with minimal (no) requirement for direct access to master, and by extension other key stakeholders, including acceptance of electronic signatures (3); local port regulation requires licensed agents conform to UNCTAD standards. |

(1) IMO Circular FAL.5/Circ.42/Rev.2

(2) Assuming formal adoption by IMO in accordance with due process.

(3) IMO regulation under development.

Does the Port Embrace Agency?

Issue

As discussed in the previous section, the engagement of a shipping agent reduces the burden of bureaucracy on the ship and, with that, the time pressure on individual crew members, notably the master.

Regulation and Standards

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has established Minimum Standards for Shipping Agents that, among other things, seek to uphold a high standard of business ethics and professional conduct among shipping agent (1). This includes:

- Negotiating and supervising the charter of a ship;

- Collection of freight and / or charter hire where appropriate and all related financial matters;

- Arrangements for Customs and cargo documentation and forwarding of cargo;

- Arrangements for procuring, processing the documentation and performing all activities required related to dispatch of cargo, including signing or endorsing cargo-related documentatio (2)

- Organising arrival or departure arrangements for the ship

- Arranging for the supply of services to a ship while in port.

In summary, an agent who meets the minimum UNCTAD standards can discharge virtually all bureaucracy related to the port process without the need for the direct involvement of the master.

This includes cargo documentation that the master may consider he or she is responsible for the authorization, but is not, i.e., self-induced time pressure.

Compliance Best Practice

|

Level 0 |

No requirement on ships’ principals to engage an agent in the port. |

|

Level 1 |

Local port regulation requires engagement of a ship’s agent. |

|

Level 2 |

In addition to Level 1, ships agents subject to licensing by the port. |

|

Level 3 |

In addition to Levels 1 and 2, local port regulation requires licensed agents conform to UNCTAD standards. |

(1) UNCTAD/ST/SHIP/13, 7 September 1988.

(2) Other than in particular circumstance, there is no requirement for the master to be involved in the process of issuing or endorsing cargo-related documentation such as the Bill of Lading albeit if the agent discharges the function, unlike the master, the agent may need to be expressly authorised to do so.

Does the Port Promote Seafarer Welfare?

Issue

Port welfare for seafarers is not a luxury. The ability to relax away from the work environment provides an essential relief of the stress and anxiety identified to have adverse impacts on performance and, with that, the probability of human error.

Regulation and Standards

MLC 2006 Regulation 4.4 encourages member states to ensure ports provide access to shore-based welfare facilities for seafarers, to secure their health and well-being. The Guidelines in Part B of the MLC Code detail the welfare facilities and services that should be provided in the port. Member states are also encouraged to increase internet access in ports and associated anchorages without cost to seafarers.

Further, the FAL Convention explicitly prohibits port states from requiring seafarers obtain visas for shore leave. The same right is enshrined in ILO Conventions 185 and 108.

Compliance Best Practice

|

NB for some ports and terminals shore leave is impractical: For example Sea Islands. In performing due diligence, account should be taken of physical limitations and the best efforts as may be made by the port to deliver welfare facilities and services within the constraints, for example provision of internet access. |

|

Level 0 |

Seafarers are explicitly prohibited from leaving the ship in port with no welfare services delivered. |

|

Level 1 |

Limited welfare services, including Wi-Fi / 5G cellular services, no shore leave. |

|

Level 2 |

Unrestricted access to MLC compliant welfare facilities and services on port premises, including free Wi-Fi / discounted cellular services, crew not permitted to leave the port premises without visa or similar. |

|

Level 3 |

MLC compliant welfare and service facilities on or off port, free Wi-Fi or cellular, proactive engagement by the port with the ship to arrange local sightseeing tours or similar, public transport passes, social events etc. |

Does the Port Proactively Engage with the Ship?

Issue

As observed in the OCIMF Marine Terminal Information Booklet: Guidelines and Recommendations (MTIB), the risk associated with bringing a ship into port can be reduced through pre-planning, ensuring ship and port personnel are fully aware of each other’s facilities, restrictions, requirements, expectations, responsibilities and authorities, particularly that of the ship’s master.

The more that issues can be resolved prior to arrival, for example stevedore briefing and awareness training(1), the less the pressure on time to deal with outstanding matters on arrival.

Regulations and standards

Other than FAL, which primarily deals with matters regulatory and trade, there are no international standards relating to pre-arrival ship – port information exchange that generally apply to all ships.

Nonetheless, the IMO Bulk Load and Unload (BLU) Code and the associated BLU Manual may be regarded to be authoritative in this respect. Likewise, the previously referenced OCIMF MTIB serves as an industry template for facilitating pre-arrival negotiations and agreement between ship and port personnel, reducing if not totally negating the need to allocate time for the process after the ship has berthed, facilitating prompt commencement of cargo operations.

Compliance and best practice

|

Level 0 |

The port offers limited information in the public domain relating to the conduct of cargo operations and / or the services on offer, with no protocol for pre-arrival communication with the ship or otherwise to exchange information / secure agreement on the conduct of cargo operations. |

|

Level 1 |

The port publishes a Port Information Guide broadly fulfilling the International Harbour Masters Association (IHMA) standards but does not engage in formalized pre-arrival negotiation with ships. |

|

Level 2 |

The port demonstrates fulfilment of the BLU Code / Manual, or similar, including agreement on a ship-shore safety checklist, ideally through a single window. |

|

Level 3 |

In addition to Level 2, the port engages a ‘customer champion’ to proactively liaise on all matters as may be raised by the ship prior to arrival, including crew welfare, with established rules / policy / procedure that unambiguously recognizes and respects the authority of the master in port. |

(1)With broadband now available on many ships, there is no reason why stevedore training cannot be delivered remotely in advance of berthing.

Does the port conform to an International Code of Safety Management?

Issue

The overall objective of a – any - Code of Safety Management is to define clear and unambiguous performance criteria, to facilitate the development, implementation, monitoring, evaluation and refinement of an effective safety management system for the purpose of controlling/minimising risk. In short, conformance to a code speaks to the commitment of port management to compliance.

Regulations and standards

There is no equivalent to the IMO International (Ship) Safety Management (ISM) Code for ports(1) albeit the ILO Code of Practice on Safety and Health in Dock Work (1977) and the ILO Guide to Safety and Health in Dock Work (1976), provides advice and assistance to those charged with the management, operation, maintenance and development of ports and their safety.

However, individually or cooperatively, several IMO member states have established port safety codes that are broadly similar to one another, specifying requirements for port safety, health and environmental management systems, i.e., to enable relevant port stakeholders to control identified risks. Among others, these include the United Kingdom, New Zealand and the Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA).

Generally, if at all, even where a national code exists, local port laws do not prescribe compliance. Nonetheless, ports may be expected to comply with the local code as a necessary prerogative to the demonstration of management commitment to safety. Moreover, nothing precludes a port from voluntary adoption of a code where no local code exists.

Compliance best practice

|

Level 0 |

There is no local port safety code nor voluntary compliance by the port with a published safety code. |

|

Level 1 |

The port has voluntary committed to a published safety code but can provide no independent verification of conformity. |

|

Level 2 |

The port has committed to a published safety code, securing certification to ISO standards associated with code requirements, for example ISO 14000 - environmental management. |

|

Level 3 |

The port has achieved a high level of excellence in international safety code conformity, demonstrated through ongoing independent risk audit of code compliance by a specialist in port safety assessment. |

(1)The relevance / impact of the ISM Code to the contractual relationship between ship owner and charterer, including the performance of counterparty due diligence, is covered elsewhere by the HEIG.

Has the port established ‘Protected Periods’ to complete essential ship safety tasks? Does the port require their completion as a condition of granting clearance?

Issue

As introduced previously, on arrival the ship must complete a number of essential tasks:

- Prior to commencing cargo operations; and,

- on completion of cargo operations before departure.

For a); these include finalizing outstanding issues with the terminal, such as hold ventilation and the ‘briefing’ of stevedores, if not completed prior to berthing.

For b); among others, stability calculations must be completed, with adjustments made to ballast if necessary – a critical risk factor for Ro-Ro ships – and the master must satisfy him or herself that the cargo has been stored and secured in compliance with SOLAS requirements – similarly risk critical in particular for Container ships.

These essential tasks beyond cargo operations require time. Time that may be viewed a non-productive ‘burden’ on the port, and as reflected in the performance standards adopted by among others the World Bank Group, inadvertently perhaps suggesting ‘failure’ by the port to maintain optimum port efficiency thus lose status[1].

Furthermore, in addition to the direct payments from ship owner to port for berth ‘overstay’, and potential breach of the lay time agreed with the charterer, depending on the circumstance, an extended period alongside may introduce wider social costs as other ships wait for the berth. To save time, and therefore costs, the master may be motivated to either not complete essential tasks or to seek to complete them at sea prior to arrival or after departure, at increased risk to ship, crew and environment.

Regulations and standards

There are no internationally adopted regulations that specifically address the issue of pre and post port cargo operations’ tasks. Nonetheless, SOLAS and associated instruments such as the ISM Code implicitly enshrine their completion in law.

Some large shipping operators, notably those involved with tankers, have established port / terminal vetting regimes that cover, in principle at least, the protocols for completing tasks pre and post cargo operations. Moreover, at least one major port (Rotterdam) has established local byelaws that prohibit seagoing vessels from lashing or releasing containers and other goods while at sea, tasks that must now only be completed while the ship is safely alongside the berth.

Compliance and best practice

|

Level 0 |

The port has no policy associated with ensuring the ship completes mandated pre and post cargo operations tasks, and / or is known to ‘force’ ships to depart the berth immediately on completion of cargo operations for example, through a punitive tariff. |

|

Level 1 |

The port does not apply punitive tariffs for non-productive time alongside but does not otherwise recognize the need for the ship to complete essential tasks on arrival / prior to departure, for example, pilots are booked for immediate completion of cargo operations. |

|

Level 2 |

The port has established policy / procedure (within the scope of a code-compliant safety management system) that formally recognizes the ship requires time to complete essential tasks pre and post cargo operations, for example, an established minimum time between completion of cargo operations and the booking marine services. |

|

Level 3 |

In addition to Level 2, the port has established local byelaws that formalise a requirement on some (or all) ships to complete mandated pre and post cargo operations tasks on the berth, i.e., banning undertaking said tasks prior to port arrival or departure, and delivers (or prescribes) services in port to complete / assist to master and crew discharge the tasks (without undue delay). |

[1] https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en/knowledge/publications/6604b7c3/us-supreme-court-provides-critical-guidance-but-leaves-key-safe-berth-question-unanswered

Where to download the guides?

Diagrams

Annexes and further reading