Working in the merchant navy can be challenging. Crew work away from home often for long periods, some with poor lines of communication to family and friends, and shipboard tasks can be demanding. The added complexity of time pressure can therefore have a very detrimental effect on people in this work environment.

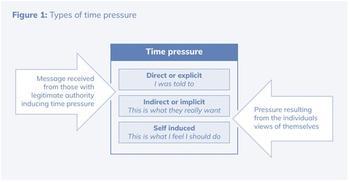

This guide has been created to raise awareness of time pressure that may be experienced in the shipboard environment, providing insight into where time pressure may come from, advice and tools that can help to deal with time pressure and insight into the systems that should prevent time pressure on board.

Managing on board

Life at sea can be challenging. The work can be demanding, crew work away from home, often for long periods, often with poor lines of communication to family and friends. The added complexity of time pressure can therefore have a very detrimental effect on people in this work environment.

What is power balance?

In a professional or personal relationship between two or more people, there will be a power dynamic. The power balance is said to be unhealthy when one person holds most or a lot of the power and it is deemed to be unfairly distributed. Experts suggest that it is healthy to strive for a dynamic where the power is fairly distributed.

Power balance

Managing a team can be extremely rewarding and good leaders are of vital importance for the effective operation of a vessel. There is the opportunity to collaborate, assume responsibility and lead, however, such a role must be executed with care. A manager position naturally holds an inherent amount of ‘power’ and whilst this is an important part of assuming higher levels of responsibility, shipboard managers should be mindful of how their rank and status could influence the actions of the people that they manage. If care is not taken, time pressure may be introduced. Psychology experts recommend striving for a fair power balance in order to promote harmony within a team.

The SMT are responsible for analysing the various demands on the vessel and crew and for allocating resources to operations and maintenance tasks. The type of vessel and the operations that it carries out will drive the tempo of the vessel. No two vessels will be the same, this requires a bespoke approach from the SMT.

For example; unscheduled repairs and maintenance to critical equipment that could result in delays to the ship schedule will likely be prioritized, this may sometimes impact the routine inspection and maintenance of less critical items. This has the potential to introduce time pressure if there is a push to catch up with planned maintenance. If the SMT believe that stress could be introduced to achieve this, they should discuss this with the owner/manager and seek assistance and guidance to rectify the situation. Once priorities are set then planning of the selected tasks can be started.

Passage planning needs to take account of whether the ship programmes allow time for major non navigational tasks. If not, then the speed may need to be adjusted or a different course taken to ensure that the ship arrives at its destination, ready and with a rested crew. Alternatively, the ship could arrive at an anchorage and not declare readiness.

In some cases, simultaneous operations (SimOps) can be used during the normal working pattern of a vessel to maintain the schedule. However, SimOps should be avoided if there are not enough personnel and/or resources to facilitate them being done safely. Trying to achieve a lot within a short space of time can promote a stressful working environment and may introduce hazards.

In the interest of safe and successful shipboard operations, it is important to consider the individuals that are being assigned to a task, some aspects for consideration include:

| Physical | Are the person(s) involved physically fit to carry out the task? |

| Fatigue | Are the person(s) involved well rested and not fatigued? |

| Mental | Do the crew feel comfortable performing the task that they have been assigned? Do they have a tendency to rush jobs or are there any personal or social pressures that may influence them? |

| Competence |

Are the person(s) suitably trained, knowledgeable and experienced to carry out the task on this vessel? Would some form of on board briefing or training be required, or should another person be substituted or brought in to supervise? |

| Familiarity with system procedures | In some cases, the person(s) involved may be new to the vessel and not be familiar with the detail of the systems and procedures in place on board the ship. |

The Safety Management System (SMS) should have a clear statement within it that describes the master’s authority in respect of maintaining the safety of crew, the environment, the vessel and the cargo.

Whilst some masters will have no reservation to exercise this authority, others may be reluctant to, for fear of possible repercussions. Masters are encouraged to use their authority where there are genuine concerns as this could prevent a life changing incident from occurring.

This authority afforded to masters under The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) has been done so in recognition that these professionals are experts in their field and should be trusted to make difficult decisions in the interest of safety. Company leaders, in addition to the Designated Person Ashore (DPA), should be expected to support masters when this special authority has been used in legitimate circumstances. Leaders and shore managers can proactively assure masters that they will be supported, in accordance with the SMS and without the threat of consequence.

Control of access (on the vessel)

There have been numerous cases where shore workers have arrived on board a vessel and entered a hazardous space with fatal consequences. It is important to remember that the vessel is responsible for the safety of third-party persons whilst they are on board.

It is not unusual for stevedores and other third parties to be keen to board as soon as the vessel is all fast. However, if the vessel is not properly prepared to receive them, there is the possibility that the crew and those third parties could feel the impact of time pressure.

Crew should be encouraged to ensure that the necessary tasks they need time to perform are done when all fast, but before the gangway is landed to ensure that crew is prepared to receive visitors.

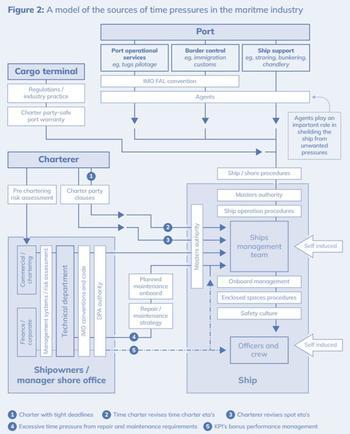

The FAL Convention aims to define standards, recommended practices and rules for simplifying formalities. Including documentary requirements and procedures in relation to a ships’ arrival, stay and departure at a port. The IMO has developed standardised forms (known as FAL Forms) for use by Governments and Authorities.

The Convention promotes the single window concept, encouraging agencies and Authorities involved in the ship’s visit to a port, to exchange information via a single point of contact, for example the ship’s agent. Since 2019 the FAL Convention has mandated that exchanges should be electronic. The benefits of the convention should translate into improved efficiencies that can alleviate the number of people that need to visit the vessel and the volume of paperwork to be completed. The agent will be able to assist the master and other senior managers with such administration, in support of controlling access to the vessel.

Management oversight of the vessel

Without effective shore side management oversight, vessels are at risk of being subject to a variety of time pressure sources.

Safety Management Systems

A crucial safeguard which can prevent crew from being impacted by stress is the SMS and how successfully it is implemented. The scope of a SMS should cover aspects that are only relevant to the vessel in question and should be written in an accessible format to encourage crew to engage with it. If done properly, crew will view their SMS as a tool that will assist them with resisting time pressure, in the event that they experience it. To assist further, it is good practice for the SMS to address time pressure as a risk and highlight the safeguards that exist to support preventing it.

An important part of successfully implementing the SMS is the master’s periodical review. This is an opportunity for the SMT and crew to provide feedback to the company about what does not work well or is not accurate within the SMS, or any other company policies and processes in place. Management of Change should be executed as a closed loop communication system, so that crew are aware of how their feedback has been considered.

Implementation of the SMS is also closely linked with leadership and organisational culture. If leaders and managers do not lead by example and are not approachable, then crew may be reluctant to speak up in the event of a non-conformity or raise the issue of time pressure.

Leaders

Leaders should be expected to demonstrate the importance of safety and its interaction with operational issues if external parties that are applying explicit pressure on the vessel or when addressing implicit pressure originating on board.

The leadership should be approachable, encourage dialogue and be prepared to change or review plans based on legitimate concerns.

Some key qualities and characteristics of good leaders are:

- Leads by example

- A mentor to team members

- Approachable

- Flexible

- Doesn’t necessarily have all the answers

- Provides constructive feedback

- Encourages people to take ownership

- Pays recognition to success of the individual or the team

- Authoritative but always fair

- Doesn’t always have to tell people what to do

The safety leadership should promote all on board to be active in identifying hazards and taking action to prevent incidents and support the concerns, observations and ideas raised by crew. The organisation should encourage a safety culture that gives high priority to individual safety with an emphasis on the right and responsibility to speak up if there is a problem or complaint.

In addition to challenging operational pressure imposed by the commercial environment, leaders also need to be alert to staff who are putting themselves under pressure. Some of this pressure may be domestic due to things such as mealtimes, shore leave or visitors, but it may also be due to a desire to impress.

Within the principles of the International Safety Management Code (ISM), the following safeguards should create a safe operating environment that would manage a wide variety of risks including excessive time pressure:

- Pre-Chartering Risk Assessment

- ‘Technical’ Management Systems and risk assessments

- Designated Person Ashore (DPA)

- Masters Authority

Pre-chartering assessment

ISM requires that all “…identified risks are adequately managed…” and this captures the risk of a vessel being fixed for a cargo for which it is fundamentally unsuited, or which places excessive time pressure on the crew. Ashore, a pre-chartering assessment, should be undertaken to confirm that the vessel is technically and operationally capable and approved to perform the scope of work required. This assessment will be completed by a competent person and should also involve input from the technical department, a designated Person Ashore (DPA) and the master, perhaps others too. Masters that do not currently take part in the pre-chartering assessment are encouraged to ask to participate. The master will be very well placed to comment on the vessel’s capability to perform a given charter and have valuable insight to contribute.

Whilst pre-chartering assessments may not be explicitly covered within the SMS, the SMS is a safeguard, a tool that can be used to justify why a vessel is or is not suitable for a given charter.

In the event that a cargo is refused by the master on the grounds of safety and compatibility with the vessel, it should be expected that shore managers will provide support and take steps to shield the vessel and crew from any undue time pressure which may result from such a decision.

Where to download the guide?

Figures and diagrams

Annex A

Annex B

Further reading