Time pressure is present in maritime shipping in many ways. Like all industries, working and delivering on time plays a crucial factor in activities within maritime shipping.

Unfortunately, this means that time pressure can sometimes be a contributing factor in the cause of maritime incidents. This focussed guide aims to highlight the presence of time pressure to stakeholders in the maritime sector. Time pressure leads to stress and as with most forms of stress, there is a balance. There is nothing wrong with setting a realistic timeframe to complete an action or task, it is when the timeframe is unrealistic that ‘excessive’ time pressure becomes a problem.

In our daily lives we often recognise the effects of time pressure. When in a hurry we may take risks that we otherwise would not, sometimes even unconsciously. Time pressure has an effect on the way we think. It tends to make us neglect our deeper knowledge and training, and sometimes may lead to potentially lethal consequences. It makes us cut corners, both literally and figuratively. One model used to describe this is ‘Fast and Slow Thinking’. An example of this can be seen in enclosed space incidents where one seafarer collapses in an enclosed space, which may have a hazardous atmosphere, and their colleague rushes to assist without thinking about the consequences. This has resulted in many deaths. Another model is the ‘Efficiency Thoroughness Trade Off’ (ETTO) which suggests that, with limited time available, some tasks may be overlooked or compressed.

The varied and conflicting demands on our time, from professional commitments to domestic responsibilities, push us to squeeze the most from every minute (Hochschild, 1997; Perlow, 1998, 1999). Modern innovations like fast food drive-throughs, mobile telephones, microwave ovens, productivity applications etc. continually increase our ability to get more done in less time. Organisations strain to make the most efficient use of their employees, laying off those who can be spared and pushing those who remain to do more in fewer hours (Schor, 1991).

Experts such as Hochschild and Schor recognize the pressure that companies are under and highlight the impacts that can be felt by their employees such as constraining cognitive capacity and impairing performance. The maritime shipping industry is not exempt from these effects. Ships are capital intensive assets and operating costs or expenses have a major impact on how the ship is run. Time pressure is a feature of many areas of ship operation and there are numerous high-profile examples: -

The request to meet a ‘challenging’ Estimated Time of Arrival/departure (ETA/ETD) can lead to shortcuts being taken or insufficient time available for voyage preparation. Some of the best-known examples include the Titanic sinking, the capsize of the Herald of Free Enterprise and more recently the grounding of Rena.

There be may pressure to berth a vessel or to unberth to clear the berth within a certain timeframe. The Hoegh Osaka capsize is a supporting example.

Pressure to complete repairs may result in rushed repairs causing damage to critical equipment or injury to crew.

Given that the existence of time pressure in general is beyond doubt, and that there is no formal recognition of time pressure within the maritime shipping industry, there is an opportunity to provide industry stakeholders with insight on the subject. To establish effective management of the risk associated with time pressure, there is a need to:

- Recognise where excessive time pressure is influencing behaviour.

- Identify where existing safeguards may be used to avoid incidents.

- Evaluate where help should be available under ISM.

This guide will detail situations, issues, and subjects to give the reader an understanding of time pressures in the maritime industry and share recommendations on how to manage them.

Time pressure

Time pressure is a form of stress that may impair a person’s ability to make safe decisions. It can be a form of ‘commercial pressure’ and businesses may struggle to find the balance between maintaining safety on board and maximizing the commercial performance of the ship. In other words, there is a fine balance between conducting operations safely and efficiently. Tilting the balance in favour of one may negatively affect the other.

It may not be apparent to individuals (or stakeholders) that their actions and/or instructions may result in time pressure being applied to staff further down the communication line. In other words, any person directly or indirectly involved with ship operations has the potential to exert time pressure. Examples include:

- Agents

- Authorities

- Charterers

- Colleagues

- Port and/or cargo workers

- Shipboard managers

- Shore based managers.

Why does time pressure happen?

Some examples of why this happens include:

- Excessive administrative demands

- Imbalance between resources and workload

- Poorly constructed or non-existent procedures

- Weak safety culture

- Lack of awareness of the effect that instructions and messaging can have on people

- Reluctance to challenge real or perceived authority

- Structure of reward programmes for seafarers

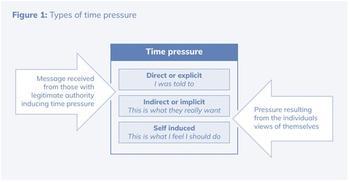

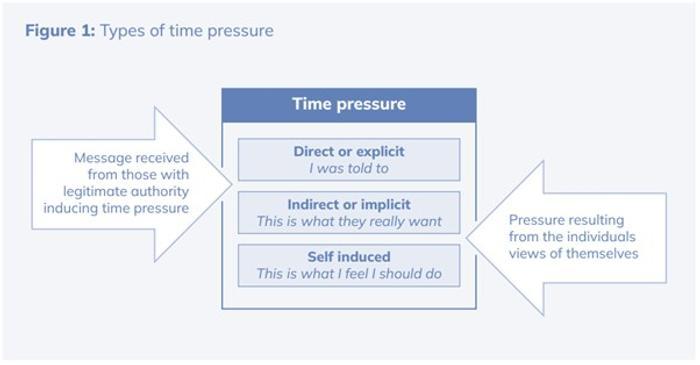

There are three different types of time pressure:

Explicit time pressure |

Implicit time pressure |

Self-induced time pressure |

|||

|

This is sometimes called direct time pressure. A formal instruction, which is time bound, is given by a party with apparent legitimate authority that creates a pressure on the receiving party to carry out the instruction within the assigned time. In some cases, this formal instruction is recorded. The situation is, therefore, visible during audits and investigations.

|

This is sometimes called indirect time pressure. In communications between parties, times are not explicitly mentioned, but are implied in the way the communication is carried out. In this case the recipient individual’s decision-making is shaped by implicit messages in the communications and processes. Sometimes, this affects people’s perceptions of what the organisation wants. Implicit time pressure is not easily visible or recordable and will seldom be visible in an investigation or audit.

|

This type of time pressure does not originate from a third party but from one’s own self. It is the perception that a task needs to be carried out within a particular timeframe determined by the individual, which is usually shorter than the desired timeframe.

|

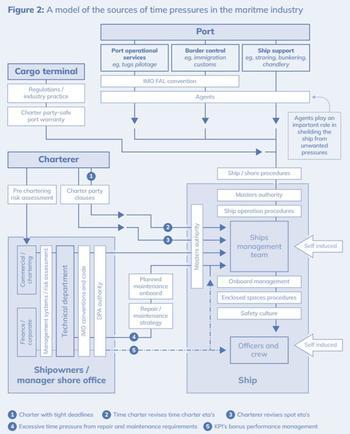

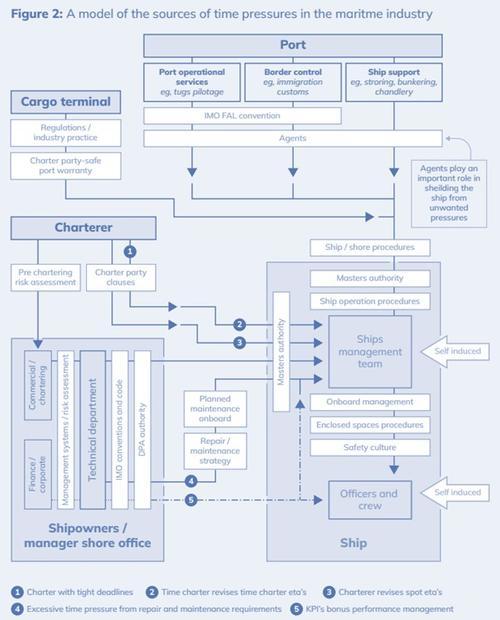

In a typical shipping company context, time pressure can arise from different sources. An analysis has been carried out to identify the various sources of time pressure and how they interact with the ship and ship-owner. The result is summarised in following model.

In the model, the grey box represents the shipping company’s shore office, and the blue box represents the ship. Arrows indicate the flow of communication - and in turn, time pressure.

Continuous arrows represent direct time pressure, broken arrows represent indirect time pressure travels. The red boxes represent existing safeguards or barriers

regulating time pressure within the system. It is important to stress that time pressure can originate from within the line of responsibility and from other outside sources.

Time pressure can arise from within the ‘Company’ (as defined in the International Safety Management Code (ISM)) or from an outside source, which then affects the company both ashore and on board. Time pressure can arise from charterers in the form of tight deadlines. A common source of time pressure is amending the time required to arrive at a port or berth, or a request to change cargoes and therefore tank/hold combinations on a tight deadline.

Ports and terminals also create time pressure on the ship – for example, by giving a ship at anchorage waiting for a berth a very short time to prepare and come alongside. If the ship requests more time, the port may assign the berth to another ship and ask the waiting ship to continue waiting for another berthing opportunity.

What does time pressure look like?

Stress due to time pressure can manifest differently between people. While some may show many physical signs, others may show only some or no signs at all.

Physical signs may include decreased energy and insomnia, headaches, weight change and change in appetite, frequent sickness, rapid heartbeat, and sweating.

Non-physical signs may include irritability and generally acting differently or changed mood. Increased complaints and grievances are another sign that may be an effect of time pressure.

Preventing time pressure

Preventing time pressure and managing expectations can go a long way to mitigating circumstances that can cause incidents. Below is a list of mitigations that can be put in place to reduce the adverse effects of time pressure.

- Understanding the sources of time pressure

- Knowing the visible signs of time pressure

- Planning and prioritising work

- Having an accessible safety management system

- Confident leaders and a healthy safety culture

- Having a strategic view of workload

- ‘STOP the job’ practices.

- Supporting the master’s authority

- Strong and open communication

- Challenging time pressure (P.A.C.E)

The Guides

Head over to the guide specific pages below for more information.